Scripps Research Team Reverses Friedreich's Ataxia Defect in Cell Culture

Newly Developed Compounds Activate Silenced Gene Responsible for Debilitating Disease

Advertisement

A team from The Scripps Research Institute and the University of California School of medicine has developed compounds that reactivate the gene responsible for the neurodegenerative disease Friedreich's ataxia, offering hope for an effective treatment for this devastating and often deadly condition. The results of the research are being published in Nature chemical biology.

In the new study, the researchers tested a variety of compounds that inhibited a class of enzymes known as histone deacetylases in a cell line derived from blood cells from a Friedreich's ataxia sufferer. One of these inhibitors had the effect of reactivating the frataxin gene, which is silenced in those with the disease. The researchers then went on to improve on this molecule by synthesis of novel derivatives, identifying compounds that would reactivate the frataxin gene in blood cells taken from 13 Friedreich's ataxia patients. In fact, one of the compounds the researchers tested produced what amounted to full reactivation of the frataxin gene in 100 percent of cells tested.

The genetic defect responsible for Friedreich's ataxia involves numerous extra repeats of a GAA-TTC triplet pattern in a person's DNA that prevent expression of the frataxin gene. Where normal cells contain 6 to 34 repeats, Friedreich's ataxia sufferers can have as many as 1,700. The more triplets a person's DNA contains, the earlier symptoms appear and the greater their severity. Several other diseases, including Huntington's disease and the spinocerebellar ataxias,are also linked to triplet repeats.

Only individuals who carry the Friedreich's ataxia defect on both of their paired alleles-i.e., who are homozygous for the trait-suffer from the condition. Those individuals who are heterozygous, with only one defective allele, produce about half the normal level of frataxin, but do not suffer disease symptoms. This suggests that a treatment for Friedreich's ataxia need not raise frataxin production all the way to normal levels to be effective.

Gottesfeld notes that the repeats causing Friedreich's ataxia are in a region of the gene that does not code for the protein frataxin, so reversing gene silencing may be all that is needed to treat the disease.

Researchers are still working to understand the reasons the triplet repeats prevent transcription of the frataxin gene, although the gene itself remains intact. Although other theories have been proposed, the new research supports an explanation known as the "histone code theory."

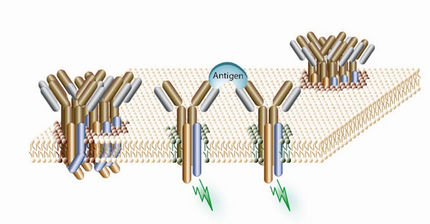

Histones are proteins that are the chief constituent of the nucleosomes around which DNA is wrapped in cells. The new theory suggests that histones must contain certain chemical cues, including acetyl groups, for nucleosomes to assume the formation that allows the genes they package to be expressed.

One idea suggested by the paper's authors is that the triplets cause an unusual DNA structure that attracts proteins such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), removing critical acetyl groups from the histones, packaging the histones in an inactive form called heterochromatin, and ultimately leading to silencing of the frataxin gene.

Based on this theory, Gottesfeld and his colleagues began looking for compounds that might block the HDACs with the goal of reactivating frataxin production. The researchers were able to draw from a range of commercially available products because many HDAC inhibitors have been developed as tools for molecular biology research and as potential cancer treatments.

Though Friedreich's ataxia impacts neuronal and muscle cells, these are not readily available for research. So, the group instead worked with white blood cells, or lymphyocytes, which are easily obtained from blood samples and can be prevented from dividing, making them a suitable proxy.

Experiments revealed that one HDAC inhibitor, called BML-210, did in fact reverse the heterochromatin formation in cultured lymphocytes from Friedreich's ataxia patients and increased the production of frataxin messenger RNA (mRNA), a precursor to production of the protein, although not sufficiently to bring protein production to normal.

Next, the researchers chemically modified BML-210 to produce a variety of analogs whose effects on the cells were then tested. One class of analogs produced a two to three-fold increase in frataxin transcription amounting to full reactivation of the frataxin gene in an astonishing 100 percent of cells from 13 Friedreich's ataxia sufferers.

Importantly, the team's HDAC inhibitors have also proven uniformly non-toxic to the lymphocytes and do not significantly affect cell growth rates. Ongoing animal studies also have not revealed any toxicity. If the results of animal testing remain positive, said Gottesfeld, the HDAC inhibitors could enter human trials as a Friedreich's ataxia treatment in as soon as 18 months' time.