New Disease Gene for Early Infantile Epilepsy found

Advertisement

A severe form of epilepsy in infants is caused by hitherto unknown mutations of the HCN1 ion channel. The changes in the genetic material are de novo mutations, i. e. they are not present in the parents. This is reported by a German-French research team in the journal “Nature Genetics”.

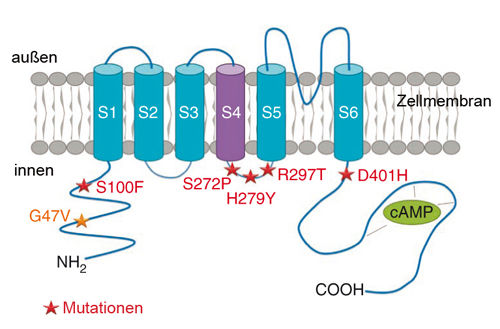

Structure of the HCN1 channel in the cell membrane of nerve cells. The asterisks mark the spots where mutations were found that cause an early infantile epilepsy resembling the Dravet syndrome.

Institute for Human Genetics, University of Würzburg

Epileptic encephalopathies are severe disorders which occur even in babies. They are accompanied by a disturbed maturation of the brain as well as by an impairment of the mental and sometimes also of the motoric development. Seizures typically appear first in combination with fever and cannot usually be treated.

Another form of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy, which has been known for some time, is the Dravet syndrome. It occurs in about one child out of 30,000 and is caused by mutations of the sodium channel gene SCN1A. However, many children suffering from a disorder resembling the Dravet syndrome have no mutations of SCNA1, so there must be other genes responsible for this early infantile type of epilepsy.

Mutations discovered in the HCN1 ion channel

In the search for new disease genes as the cause of early infantile epileptic encephalopathies, scientists from Paris and Würzburg have now made a discovery. In the genetic material of nearly 200 affected children, where mutations of the SCNA1 gene had already been ruled out, they discovered in six cases the pathogenic mutations in another ion channel gene, namely HCN1. These dominant mutations arise spontaneously during the generation of the parents' reproductive cells; they are not present in the parents' body cells.

“The electric current carried by the HCN1 cation channel is also referred to as 'pacemaker', because it stimulates rhythmic activity in spontaneously active nerve cells”, says Professor Thomas Haaf, head of the Institute for Human Genetics of the University of Würzburg Animal models had already suggested that this channel has a key role in epileptic disorders. “But so far no corresponding mutations had been found in patients.”

Differences from the Dravet syndrome

At the beginning the seizures of children with mutations of the HCN1 gene are hardly distinguishable from the Dravet syndrome, but at later stages they are: “There is an increased occurrence of atypical seizures. All affected children have an impairment of intelligence and behavioural disorders, including autistic behaviour”, says Professor Haaf.

The study was led by Dr. Christel Depienne, who worked for two years until the end of 2013 as a visiting scientist at the Würzburg Institute for Human Genetics. From there she coordinated the German-French research team.

Consequences of the new discovery

How can patients benefit from the new findings? This is not an easy question to answer, because it is usually a long way from the discovery of a pathogenic gene mutation to the therapy.

Professor Haaf comments: “In any case, a better understanding of the molecular causes of the disorder will be helpful in the development of new therapeutic approaches, for example of drugs with a specific effect on the HCN1 currents. The results enable us already to make a correct diagnosis of this very severe early infantile disorder, which usually occurs sporadically, and to provide genetic counselling to parents with regard to their further family planning.”