People main cause behind spread of dangerous viroids in plants

Advertisement

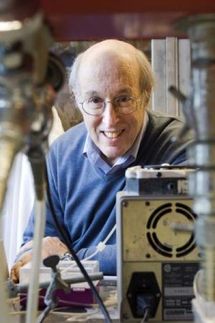

The dangerous potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd) mainly ends up in tomato plants as a result of human actions. The main source of infection appears to be ornamental shrubs, with infection via seeds rarely if ever playing a role. These conclusions are published in the dissertation of Koo Verhoeven with which he obtained his doctoral degree at the Wageningen University, part of Wageningen UR, on June 2.

“Viroids are miniscule pathogens that consist of only one RNA molecule,” says Verhoeven, employee at the Dutch Plant Protection Service (PD). “In comparison: A virus is a DNA or RNA molecule covered with a protein shell. Scientists were not able to determine the nature and presence of viroids until the 1970s.”

Verhoeven developed a molecular-biological technology that can relatively easily determine whether tomato plants are infected with viroids. He extracts the RNA of viroids from samples and further analyses it to determine the presence of viroids. One of the results was Verhoeven’s discovery of a new viroid in capsicum plants.

The main viroid in the Netherlands is the potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd), which causes growth inhibitions, discolouration and deformities in tomatoes and potatoes. Not all crops that carry PSTVd actually become diseased says Verhoeven. “Specific ornamental shrubs such as Solanum jasminoides, commonly known as the potato vine, are not sensitive to the viroids. As a result it is impossible to see if plants are infected, making them a dangerous source of infection.”

In stark contrast, tomato and potato plants are highly sensitive to PSTVd. Verhoeven discovered that the tomato in particular was easily infected with PSTVd by people. Fingers which have touched leaves of viroid-carrying ornamental shrubs can transmit them to tomato plants up to two hours after contact. Viroids can also be spread by tools such as the small knives used to cut shoots from plants.

In the outbreaks studied by Verhoeven, the viroids in the plants were shown not to have originated from the used tomato seeds. Verhoeven was also involved in research into the role of insects such as bumblebees and thrips in the transfer from ornamental shrubs to tomato plants. The results showed that they were not a major source of infection. “Tomato plants infected with PSTVd were most likely infected by people bringing the viroid into the greenhouse from outside,” says Verhoeven.

Verhoeven’s conclusions are important to both breeders and breeding companies. Breeders should be able to organise their activities in such a way that the risk of spreading the viroids is as limited as possible. Breeding companies could be more assured that their products are not a source of PSTVd infection and use Verhoeven’s findings to prevent viroids from ending up in seed production.

The test Verhoeven developed is of interest to the international trade and the organisations that carry out the related phytosanitary checks, such as the Dutch Plant Protection Service (PD) and the inspection services. Now that it is known which viroids occur in tomatoes, what the major sources of infection are and how the viroids are spread, all the essential data for making a Pest Risk Analysis is available. Based on such an analysis, governments can make more substantiated decisions in granting a quarantined status. Such a status offers extra guarantees that the plant material on the market is not contaminated with specific organisms. It can also result in the compulsory destruction of crops, fruits and seeds, even if they are not visibly affected by the infection.