Insights into olfactory disorders in Alzheimer's disease

Advertisement

A diminishing sense of smell can be one of the earliest signs of Alzheimer's disease, even before cognitive impairment occurs. Studies by researchers at the DZNE and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU) provide new insights into this phenomenon. According to the study, the brain's immune response plays an important role, as it apparently attacks nerve fibers that are important for the perception of odors.

The study, published in the journal "Nature Communications", is based on observations in mice and humans, including analyses of brain tissue and so-called PET scans. These findings could help to develop methods for early detection and therefore early treatment.

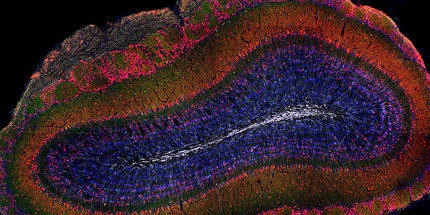

According to the researchers, these olfactory disorders arise when immune cells in the brain, known as microglia, remove connections between two regions of the brain - the olfactory bulb and the locus coeruleus. The olfactory bulb is located in the forebrain and analyzes sensory information from the olfactory receptors in the nose. The locus coeruleus, a region in the brain stem, influences this processing by means of long nerve fibers that extend from nerve cells in the locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb. "The locus coeruleus regulates a variety of physiological mechanisms. These include blood flow to the brain, sleep-wake rhythms and sensory processing. The latter applies in particular to the sense of smell," says Dr. Lars Paeger, a scientist at the DZNE and LMU. "Our study suggests that in the early phase of Alzheimer's disease, changes occur in the nerve fibers that connect the locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb. These changes signal to the microglia that the affected fibers are defective or redundant. As a result, they are degraded by the microglia."

Changes in the membrane

Specifically, the team led by Dr. Lars Paeger and Prof. Dr. Jochen Herms, co-author of the current publication, found evidence of an altered composition of the membranes of the affected nerve fibers. The fatty acid phosphatidylserine, which is normally found on the inside of the membrane of nerve cells, had migrated to the outside. "The presence of phosphatidylserine on the outer side of the cell membrane is known as the 'eat-me signal' for microglia. In the olfactory bulb, this is usually accompanied by a process known as synaptic pruning. This serves to remove unneeded or dysfunctional neuronal connections," explains Paeger. "In our case, we assume that the change in membrane composition is triggered by hyperactivity of the affected nerve cells due to Alzheimer's disease. This means that these cells fire in an abnormal way, i.e. send out signals."

Extensive data

The findings of Paeger and his colleagues are based on a large number of observations. These include studies on mice with characteristics of Alzheimer's disease, the analysis of brain samples from deceased people with Alzheimer's as well as examinations of the brains of people with Alzheimer's or mild cognitive impairment using positron emission tomography (PET). "Odor disorders in Alzheimer's disease and damage to the associated nerves have been the subject of discussion for some time. However, the causes were previously unclear. Our results now point to an immunological mechanism as the trigger - and in particular that these processes already start in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease," says Jochen Herms, research group leader at the DZNE and LMU and member of the Munich Cluster of Excellence "SyNergy".

Prospects for early diagnosis

So-called amyloid-beta antibodies have recently become available against Alzheimer's disease. In order to be effective, this novel therapy must be used at an early stage of the disease - and this is precisely where the current research results could be of significance. "Our findings could pave the way for identifying patients who develop Alzheimer's disease at an early stage so that they can then undergo complex diagnostics and confirm the diagnosis before cognitive problems occur. This could enable earlier intervention with amyloid beta antibodies - with a correspondingly higher probability of response," says Herms.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.

Original publication

Carolin Meyer, Theresa Niedermeier, Paul L. C. Feyen, Felix L. Strübing, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Katerina Karali, Johanna Gentz, Yannik E. Tillmann, Nicolas F. Landgraf, Svenja-Lotta Rumpf, Katharina Ochs, et al.; "Early Locus Coeruleus noradrenergic axon loss drives olfactory dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease"; Nature Communications, Volume 16, 2025-8-8