Duke technique is turning proteins into glass

Advertisement

Duke University researchers have devised a method to dry and preserve proteins in a glassified form that seems to retain the molecules' properties as workhorses of biology. They are exploring whether their glassification technique could bring about protein-based drugs that are cheaper to make and easier to deliver than current techniques which render proteins into freeze dried powders to preserve them.

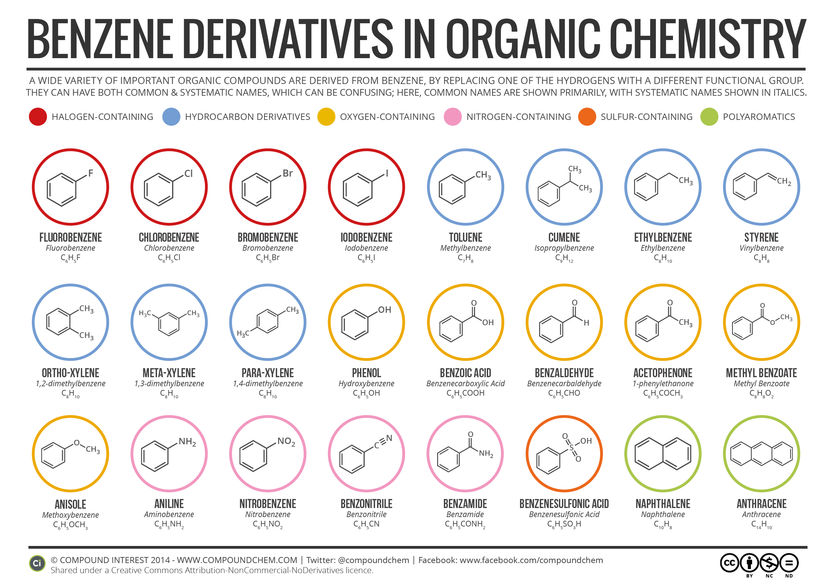

Duke engineer and chemist David Needham describes this glassification process as "molecular water surgery" because it removes virtually all the water from around a dissolved protein by almost magically pulling the water into a second solvent.

"It's like a sponge sucking water off a counter," said Needham, a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke's Pratt School of Engineering, who has formed a company called Biogyali ("gyali" means glass in Greek) to develop the innovation. That firm has also applied to patent the idea of turning proteins into tiny glass beads at room temperature for drug delivery systems.

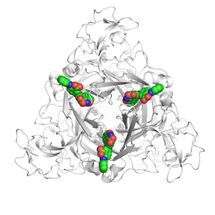

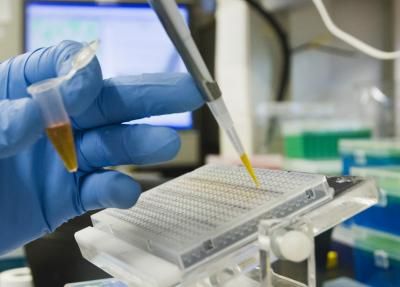

A report by Needham, graduate student Deborah Rickard and former graduate student P. Brent Duncan in the Biophysical Journal describes how his team carefully controlled water removal during glassification by releasing single tiny droplets of water-dissolved protein into the organic solvent decanol with a micropipette.

Preliminary evaluations by his senior scientist David Gaul and a team of undergraduate students showed that four test proteins undergoing such procedures retained all or most of their original activity when water was restored. His group has received about $1 million from the National Institutes of Health grants for the research.

Having devised a way to turn proteins into glassy microbeads measuring only about 26 millionths of a meter in diameter, Needham hopes those can be directly injected into the body for use as "biologic" drugs.

His group's early research shows high concentrations of such tiny beadlets would not be as viscous as proteins dehydrated into the normal powder form, which tend to clog up syringes, he said.

These microbeads might also be packaged for slow time-release by surrounding them with a polymer that would biodegrade over time, though how to do that has not been resolved yet, he added. In collaborations with Duke's Brain Tumor Center and Comprehensive Cancer Center, the researchers are seeking additional funding to do initial evaluations on glassified forms of three molecules with drug potential.

Original publication: Deborah L. Rickard, P. Brent Duncan, and David Needham; "Hydration Potential of Lysozyme: Protein Dehydration Using a Single Microparticle Technique"; Biophysical Journal 2010; Volume 98, Issue 6, 1075-1084.