How bacteria resist enemy attacks

However, protection against rivals reduces resistance to medication

Advertisement

Some bacteria use a molecular harpoon to eliminate their rivals. They inject them with a deadly cocktail. Researchers at the University of Basel have now discovered that some bacteria can protect themselves from the poison cocktail of their attackers. However, this makes them more susceptible to antibiotics.

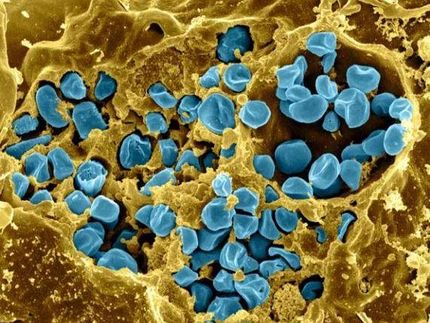

Bacteria of different species usually live together in millions and millions in the smallest of spaces. This means that a battle for space and resources is inevitable. To assert themselves, some bacteria rely on a molecular harpoon with which they literally outdo their opponents. One of these bacteria is Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It is widespread in the environment, but is also considered a problem germ in hospitals.

Pseudomonas can live in peaceful coexistence with other microbes. However, if it is attacked by foreign bacteria with a nano-harpoon, it assembles its own in a matter of seconds. With this so-called type VI secretion system (T6SS), it injects the attacker with its own deadly poison cocktail.

But how can Pseudomonas fight back at all if it has already been injected with its own poison by the enemy? The team led by Prof. Dr. Marek Basler at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel has found an answer and has now published its findings in the journal "Nature Communications".

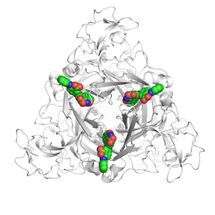

Attack activates emergency program

The deadly cocktail consists of a mixture of toxic proteins that attack various sites in the bacteria. These include enzymes that damage the cell membrane or destroy the protective cell wall. Others break down the genetic material. "These toxic proteins usually target many vital processes and cell structures," says Alejandro Tejada-Arranz, first author of the study. "However, Pseudomonas has antidotes that render the toxic mixture harmless." After an attack, Pseudomonas can therefore evade the effect of the toxin and actively counterattack.

Bacteria are generally immune to toxins from close relatives. In the case of T6SS attacks from foreign bacteria, however, Pseudomonas activates an emergency program that initiates a variety of protective measures within a very short time. "Concerted actions are taken, all aimed at repairing the damage caused and intercepting toxic proteins," says Tejada-Arranz. "For example, the bacteria resort to a membrane protein that stabilizes the damaged outer cell envelope."

The range of measures makes Pseudomonas resistant to the various toxins of its attackers. Its ability to assert itself in bacterial communities could possibly also play a role in problematic infections.

Resilience comes at the expense of antibiotic resistance

However, this resilience comes at a price. "We initially thought that bacteria that are so good at defending themselves would also be less sensitive to antibiotics," explains Marek Basler. "Surprisingly, the resistance comes at the expense of their antibiotic resistance. The bacteria obviously have to make trade-offs and cannot protect themselves against all threats at the same time."

In the community, Pseudomonas bacteria are presumably broadly positioned: some are better protected against T6SS attacks, others against antibiotics. So some bacteria always survive. "Our work shows that Pseudomonas has a whole range of different protective mechanisms," says Basler. "We don't yet know whether they also play a role in human infections. Do the strategies help Pseudomonas in bacterial communities as they occur in infections? And what does this mean for antibiotic therapies? These are still open questions."

The study, led by Marek Basler, was carried out as part of the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) "AntiResist", which aims to develop alternative strategies to combat antibiotic-resistant germs.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.