Research sheds light on workings of anti-cancer drug

Crystal structure shows how drug disables harmful copper in cells

Advertisement

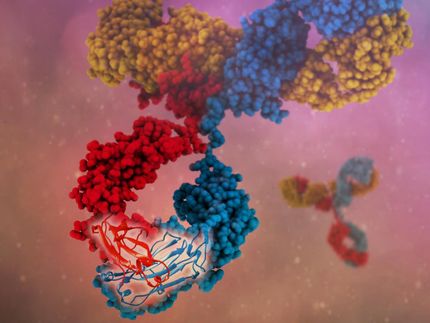

The copper sequestering drug tetrathiomolybdate (TM) has been shown in studies to be effective in the treatment of Wilson disease, a disease caused by an overload of copper, and certain metastatic cancers. That much is known. Very little, however, is known about how the drug works at the molecular level. A new study led by Northwestern University researchers now has provided an invaluable clue: the three-dimensional structure of TM bound to copper-loaded metallochaperones. The drug sequesters the chaperone and its bound copper, preventing both from carrying out their normal functions in the cell. For patients with Wilson disease and certain cancers whose initial growth is helped by copper-dependent angiogenesis, this is very promising.

This knowledge opens the door to the development of new classes of pharmaceutical agents based on metal trafficking pathways, as well as the further development of more efficient TM-based drugs. The study is published in Science Express.

"Essential metals are at the center of many emerging problems in health, medicine and the environment, and this work opens the door to new biological experiments," said Thomas V. O'Halloran, the study's senior author and the Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor of Chemistry in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern. He and geneticist Valeria Culotta of Johns Hopkins University discovered the first copper chaperone function in 1997.

O'Halloran and his research team studied the copper chaperone protein Atx1, which provides a good model of copper metabolism in animal cells. "We wondered what the drug tetrathiomolybdate did to copper chaperones - proteins charged with safely ferrying copper within the cell - and what we found was most amazing," O'Halloran said. "The drug brings three copper chaperones into close quarters, weaving them together through an intricate metal-sulfur cluster in a manner that essentially shuts down the copper ferrying system."

The nest-shaped structure of the metal-sulfur cluster discovered by the researchers was completely unanticipated.

"When we mixed TM together with copper chaperone proteins in a test tube, the color of the solution changed from light orange to deep purple," said Hamsell M. Alvarez, the paper's first author and a former doctoral student in O'Halloran's lab, now with Merck & Co., Inc. "The sulfur atoms in the tetrathiomolybdate bound to the copper atoms to form an open cluster that bridged the chaperone proteins. In this manner, three copper proteins were jammed onto one thiomolybdate."

Alfonso Mondragón, professor of biochemistry, molecular biology and cell biology in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, and graduate student Yi Xue, both co-authors of the paper, solved the three-dimensional crystal structure using protein X-ray crystallography. This is the first example of a copper-sulfide-molybdenum metal cluster protein.

Based on the structure and additional experiments, the scientists propose that the drug inhibits the traffic of copper within the cell because of its ability to sequester copper chaperones and their cargo in clusters, rendering the copper inactive.

"We conclude that the biological activity of tetrathiomolybdate does not arise from a simple copper sequestering action but through a disruption of key protein-protein interactions important in human copper metabolism," Alvarez said.

The chain of discovery that led to the use of tetrathiomolybdate as a therapeutic agent began in the 1930s when cows grazing in certain types of pastures in England developed neurological problems. This trouble was then linked to other neurological problems with sheep grazing on certain soils in Australia. It was found that molybdate, a non-toxic compound present in the grass of these pastures, when consumed in excessive amounts by the ruminants, led to copper deficiencies and neurological problems in the animals.