Two accomplices in the spotlight: When the interaction between fungi and bacteria becomes a dangerous alliance

Researchers discover new co-infection strategies of Candida albicans andEnterococcus faecalis

Advertisement

Rivals or allies – how do bacteria and fungi interact in our bodies? Until now, bacteria on our mucous membranes were primarily considered to be antagonists of fungi, as they can inhibit their growth. However, an international research team led by the Leibniz-Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology (Leibniz-HKI) in Jena has now been able to show that the yeast Candida albicans and the bacterium Enterococcus faecalis form a dangerous alliance under certain conditions: Instead of fighting each other, they can amplify their impact and cause significantly more severe cell damage together than alone. In the study now published in the journal PNAS, the researchers reveal the mechanisms behind this – and the crucial role of the bacterial toxin cytolysin.

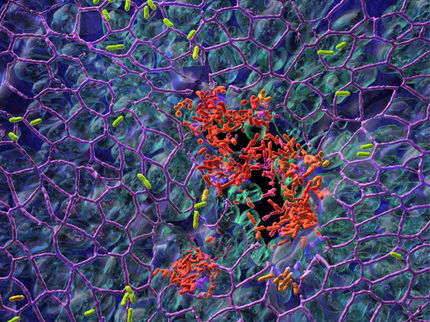

Scanning electron microscope image: Bacteria of the species Enterococcus faecalis (purple) attach to hyphae of the fungus Candida albicans (turquoise).

© Leibniz-HKI

The yeast Candida albicans and the bacterium Enterococcus faecalis are usually harmless inhabitants of our mucous membranes. However, if the immune system is weakened or the microbial balance is disturbed—for example, after antibiotic therapy—they can cause infections. The severity of an infection also depends on how the two microbes interact with each other. “Most studies examine how bacteria and fungi inhibit each other,” says Ilse Jacobsen, head of the Department Microbial Immunology at Leibniz-HKI. “We wanted to know why they cooperate under certain conditions, thereby causing significantly more damage, and what factors influence this.”

Cytolysin as a key factor

To understand this cooperation better, the team tested numerous E. faecalis strains in cell culture models. They found that only some of them significantly increased cell damage when infected simultaneously with Candida albicans. These strains shared a striking characteristic: they produced cytolysin, a toxin that perforates cell membranes and thus kills the cells. If the corresponding gene was missing in the bacterium, the additional damage did not occur. When it was added, the effect reappeared. The findings from the cell cultures were also confirmed in the mouse model. Cytolysin-producing bacterial strains increased the damage to the mucous membrane caused by Candida albicans, while variants without the toxin even had a mitigating effect. “Not all enterococci are the same,” emphasizes Jacobsen. “Here, the cytolysin-producing variants have proven to be the dangerous ones. This explains why more severe disease progressons are sometimes observed, even though the same microorganisms are involved in the clinical samples.”

How the collaboration works

In addition to the central role of cytolysin, the research team identified two main mechanisms that explain the dangerous alliance between the two microbes:

- Direct contact: The bacteria attach themselves to the fungal cells and thus come into close contact with the host cells. This allows the bacterial toxin cytolysin to act exactly where it causes most of the damage.

- Nutrient depletion: Candida albicans consumes sugar (glucose) particularly quickly. The resulting energy deficiency weakens the host cells and makes them more susceptible to the bacterial toxin.

In this way, the fungi and bacteria together create an environment in which they can fully unleash their destructive effects and cause massive cell damage – an impressive example of how complex microbiological interactions shape the course of an infection.

“The results of our study show that the danger of an infection depends not only on a single species, but on which microbes encounter each other and which tools they use,” says Jacobsen. “This helps us to better understand why some infections are so severe and could, in the long term, help to develop more targeted therapies against combined infections.”

Original publication

Kapitan M, Niemiec MJ, Millet N, Brandt P, Chowdhury MEK, Czapka A, Abdissa K, Hoffmann F, Lange A, Veleba M, Nietzsche S, Mosig AS, Löffler B, Marquet M, Makarewicz O, Kline KA, Vylkova S, Swidergall M, Jacobsen ID (2025) Synergistic interactions between Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis promote toxin-dependent host cell damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 122(46), e2505310122.