Why Zika and dengue viruses are preferentially transmitted through blood

Advertisement

Why is infection with the zika virus and other pathogens more likely to occur through insect bites than through saliva or semen, even though the virus is present in them? An international research group led by the universities of Marburg and Ulm has elucidated the mechanism that blocks the viruses in these bodily fluids.

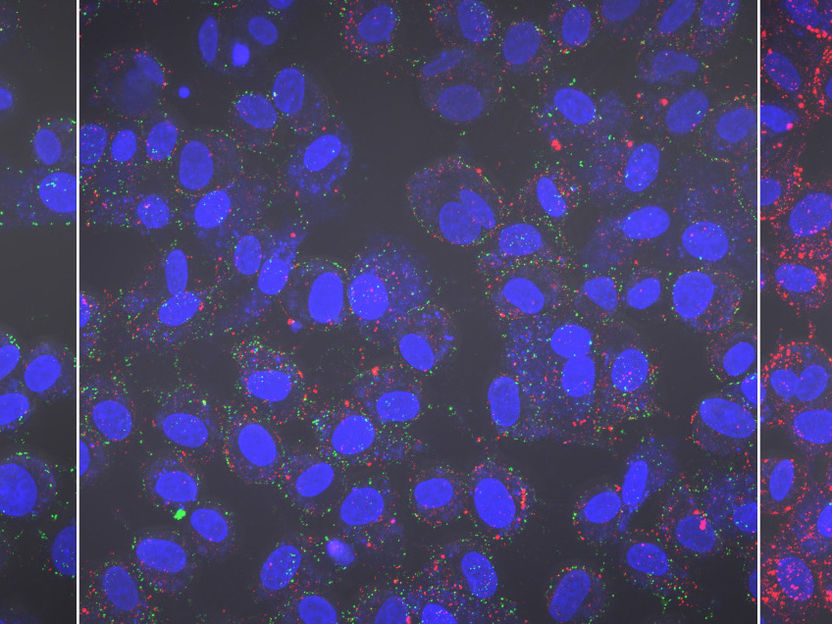

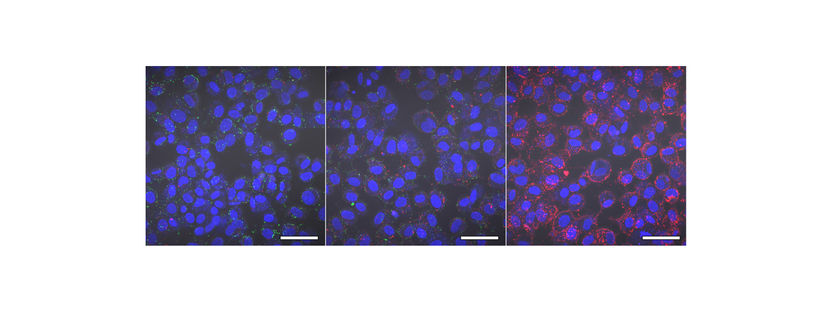

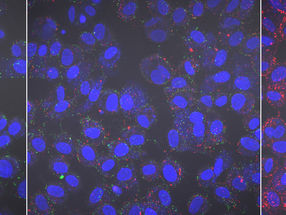

Attachment of Zika virus particles (green) and extracellular vesicles from seminal fluid (red) to target cells (cell nuclei in blue) with increasing vesicle concentrations from left to right

Foto: Rüdiger Groß

Attachment of Zika virus particles (green) and extracellular vesicles from seminal fluid (red) to target cells (cell nuclei in blue) with increasing vesicle concentrations from left to right

Foto: Rüdiger Groß

The Zika virus is mainly found in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia. It causes fever, rashes and joint pain, but can also cause damage to fetuses if pregnant women are infected. The virus is usually transmitted by mosquitoes. "Transmission is very rarely oral or sexual, although the virus is present in body fluids such as saliva and semen," explains Marburg virologist Professor Dr. Janis Müller, the lead author of the specialist article.

Why is it that some virus-contaminated body fluids rarely lead to infection? As Müller's research group discovered, membrane vesicles, known as extracellular vesicles, which are also found in saliva and semen, are responsible for this. Until now, however, it was not known how these vesicles prevent viral infection, nor which other viruses this applies to.

Janis Müller's team joined forces with scientists from all over Germany, Europe and the USA to solve the puzzle. The research group discovered that the virus-inhibiting effect is based on a specific molecule, namely the fatty molecule phosphatidylserine, which the vesicles carry on their surface.

The counterpart of this molecule on the body cells - a phosphatidylserine receptor - normally helps Zika viruses to infect. The viruses dock onto these receptors in order to penetrate the cells. "The vesicles prevent this because they also attach to these receptors," explains Dr. Rüdiger Groß from the University of Ulm, first author of the study: "Extracellular vesicles, which carry phosphatidylserine on their outer surface, compete with the viruses for the entry port - and they are present in quantities over 10,000 times greater than virus particles." As a result, the Zika viruses cannot find a way into the body's cells.

"We have thus identified a completely new defense mechanism in the body," emphasizes Müller. The research team tested whether the vesicles also prevent other viruses with similar entry mechanisms from infecting the body under laboratory conditions. This actually applies to Ebola and dengue viruses as well as other pathogens, but not to HIV-1, SARS-CoV-2 and herpes viruses - these use different entry ports.

"The newly discovered mechanism also explains why the transmission of Zika and dengue viruses by blood-sucking insects is more likely," explains Müller: "The blood contains hardly any phosphatidylserine-exposing vesicles."

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.

Original publication

Rüdiger Groß & al.: Phosphatidylserine-exposing extracellular vesicles in body fluids are an innate defense against apoptotic mimicry viral pathogens, Nature Microbiology 2024, URL: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-024-01637-6