It’s all about the right balance

New findings provide a structural framework for the development of new cancer-therapeutic strategies

Advertisement

Collaborative work of research groups at the University of Würzburg and the TU Dresden has provided important new insights for cancer research. During cell division specific target proteins have to be turned over in a precisely regulated manner. To this end specialized enzymes label the target proteins with signaling molecules. However, the enzymes involved in this process can also label themselves, thus initiating their own degradation. In a multidisciplinary approach, the researchers identified a mechanism of how enzymes can protect themselves from such self-destruction and maintain sufficient concentrations in the cell.

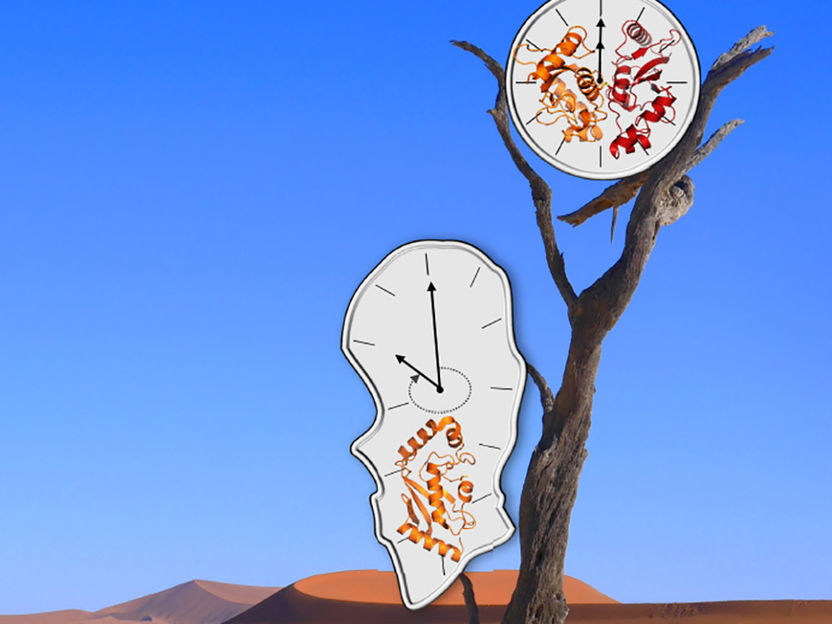

Surrealistic take on the enzyme UBE2S, which regulates its lifetime by switching between a monomeric and a dimeric state.

© Anna Liess

Vital functions of the multicellular organisms, such as growth, development, and tissue regeneration, depend on the precisely controlled division of cells. A failure in the underlying control mechanisms can lead to cancer. A team of researchers led by Dr. Sonja Lorenz from the Rudolf Virchow Center - Center for Integrative and Translational Bioimaging at the University of Würzburg and by Dr. Jörg Mansfeld from the Biotechnology Center (BIOTEC) at the Technical University of Dresden discovered a new mechanism that modulates cell division.

Ubiquitination – a central regulatory element

A critical step in cell division is the distribution of the genetic information evenly between the daughter cells. This process is controlled by a large protein complex, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), which labels proteins with a signaling molecule known as “ubiquitin”. The ubiquitin label functions essentially as a molecular postal code, targeting labeled proteins to the cellular protein degradation machinery. To allow for the efficient and precise labeling of target proteins, the APC/C works together with an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, UBE2S. However, UBE2S also has the ability to modify itself with ubiquitin, thus initiating its own degradation. This ability applies to ubiquitination enzymes in general. “This raises the fundamental question of how ubiquitination enzymes find the right balance between labeling their targets and labeling themselves to ensure that sufficient quantities of the enzymes are available in the cell,” says Sonja Lorenz.

Switching between active and inactive states

The new study provides an answer to this question by showing that UBE2S can adopt an inactive state in which it is unable to label itself with ubiquitin. "When UBE2S forms a dimer, i.e., two molecules pair with each other, they become inactive and protected from self-destruction," says Jörg Mansfeld. The scientists suggest that this mechanism ensures that a stable cellular pool of UBE2S is preserved and re-activated when required. The cell can thus control the ratio of active and inactive UBE2S to fine tune cell division. These findings provide a structural framework for the development of new cancer-therapeutic strategies and drug discovery.