NIH grant advances Tay-Sachs disease gene therapy

Families' donations crucial to start-up of Boston-based research consortium

Advertisement

In a victory for families who dug into their own pockets to fund new research, the National Institutes of Health has awarded a $3.5-million grant to the Boston-based Tay-Sachs gene therapy Consortium to prepare a gene therapy for human clinical trials in a bid to halt the fatal genetic disorder. With a plan to initiate human trials within four years, the NIH award was eagerly awaited by Tay-Sachs families and their supporters, who raised nearly $600,000 to assemble the international consortium of experts and help maintain its research agenda while scientists worked to secure federal funding. The NIH grant will help advance the gene therapy from animal tests to human clinical trials.

"The consortium has been held together with funds raised by people affected by this terrible disease," said Boston College Professor of Biology Thomas Seyfried, whose lab is part of the consortium. "People were pounding the pavement raising money. It was critical to our work and for these families, who have lost children, who have a vested interest in this research."

In addition to the Seyfried lab, the consortium includes University of Massachusetts Medical School professor and project manager Miguel Seña-Esteves, Dr. Tim Cox, University of Cambridge (U.K.), Dr. Florian Eichler, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Auburn University Professor Doug Martin.

A fatal genetic disorder most often found in children of Eastern European Jewish descent, Tay-Sachs typically claims its victims before they reach age 5. There are variants that affect children of Irish and French-Canadian descent as well. While genetic screening has greatly reduced deaths from Tay-Sachs, approximately 25-30 individuals die from the disease annually. Infants can show signs of the disease as early as six months, cease meeting developmental milestones, and then begin to lose motor skills. Children affected by juvenile onset show signs after age three and quickly begin to regress physically and mentally. Most children do not survive past age 5. For adults afflicted by late onset Tay-Sachs, symptoms are often confused with mental illness or other diagnoses.

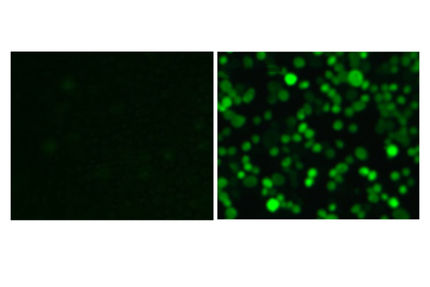

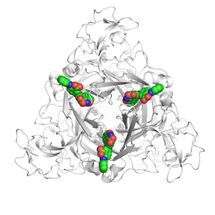

Tay-Sachs disease creates an enzyme deficiency that allows harmful quantities of a fatty substance, or lipid, to build up in the nerve cells of the brain, resulting in a relentless deterioration of mental and physical abilities. Consortium researchers say their therapy will battle the disease at the cellular level.

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Gene therapy

Genetic diseases once considered untreatable are now at the center of innovative therapeutic approaches. Research and development of gene therapies in biotech and pharma aim to directly correct or replace defective or missing genes to combat disease at the molecular level. This revolutionary approach promises not only to treat symptoms, but to eliminate the cause of the disease itself.

Topic world Gene therapy

Genetic diseases once considered untreatable are now at the center of innovative therapeutic approaches. Research and development of gene therapies in biotech and pharma aim to directly correct or replace defective or missing genes to combat disease at the molecular level. This revolutionary approach promises not only to treat symptoms, but to eliminate the cause of the disease itself.