A finishing school for proteins: Deciphering the conformational cycle of the chaperone BiP

Advertisement

proteins form the labor force of the cell. Each protein can perform its particular function only if it folds into a specific shape. So-called chaperones intervene, often during protein synthesis, to prevent misfolding. A team led by Professors Johannes Buchner of the Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM) and Don C. Lamb of the LMU Munich have now taken a closer look at how a major chaperone called BiP performs this role. The researchers specifically asked how BiP’s conformation changes from the moment it binds to a substrate up until the substrate is released and how the co-chaperone ERdJ3 influences its functional cycle. They present their findings in Nature Structural & molecular biology.

Chaperon BiP

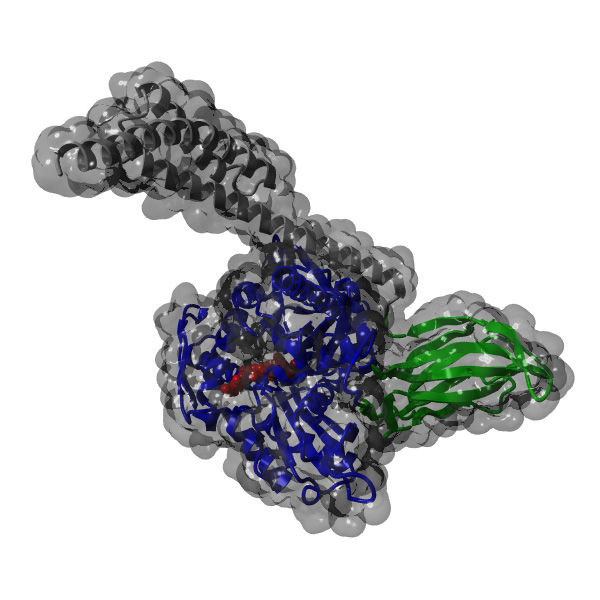

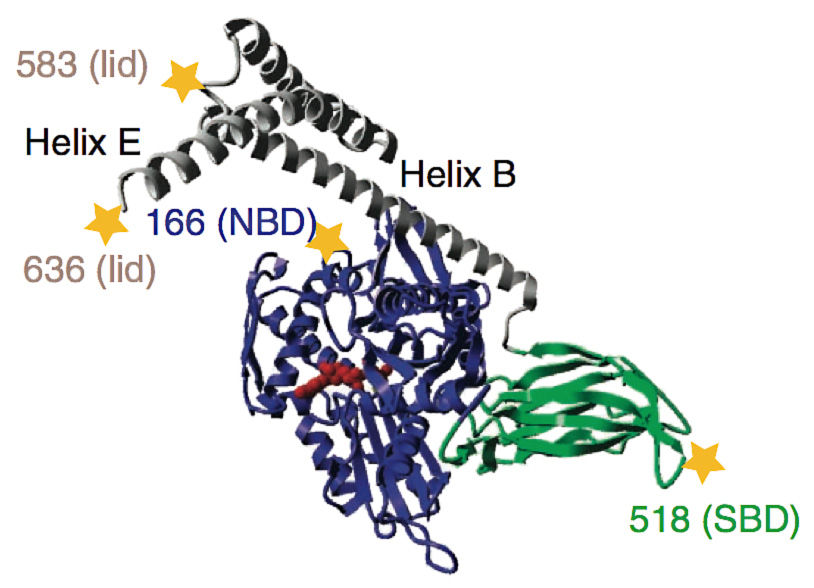

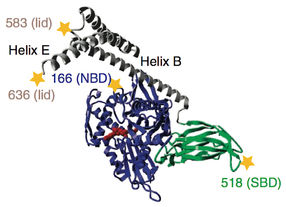

Chaperon BiP: stars mark the positions of fluorophoren for the FRET measurements.

Folding, assembly and quality control of about one-third of all proteins take place in the so-called endoplasmic reticulum, a system of linked membranous tubes within the cell. Molecular chaperones, including the protein BiP, play a decisive role in all of these processes, helping their substrates to find their correct shapes. Interestingly, chaperones also seem to facilitate protein degradation. Based on measurements taken using the Fluorescence-Resonance-Energy-Transfer (FRET) method, the scientists showed that BiP consists of two distinct domains, each of which influences the structure, and so also the function, of the other.

One of the domains binds substrates and has a kind of a molecular lid. The study revealed that when BiP was bound to an authentic substrate protein, this lid was held in an open position. On the other hand, when a short protein fragment (in this case, a peptide consisting of only seven amino acids) bound to the chaperone, the lid closed.

“This finding is interesting because the pharmaceutical industry often uses only short peptides, rather than whole proteins, for binding tests, because they are much easier to handle,“ says Professor Don C. Lamb of the Department of Chemistry at LMU Munich. “We have now clearly shown that BiP can discriminate between a short peptide and a long unfolded protein molecule, even though it recognizes and interacts with the same amino acid sequence in both cases.“

Exactly how the molecular lid behaves is dependent on BiP’s accessory protein ERdJ3. This cochaperone itself binds to BiP and facilitates its interaction with substrates by keeping the lid in a protein-accepting state.

“Our results demonstrate that ERdJ3 essentially puts the chaperone in a

position to bind its natural substrates,” says Professor Buchner from the Department of Chemistry at TUM. “In fact, the co-chaperone interacts directly with several regions of BiP. Overall, our findings indicate that the function of BiP involves complex and intricate interactions between the chaperone co-chaperone and substrate.“