Cell-free production of bacteriophages

Viruses help combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria

Advertisement

More and more bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics. bacteriophages are one alternative in the fight against bacteria: These viruses attack very particular bacteria in a highly specific way. Now a Munich research team has developed a new way to produce bacteriophages efficiently and without risk.

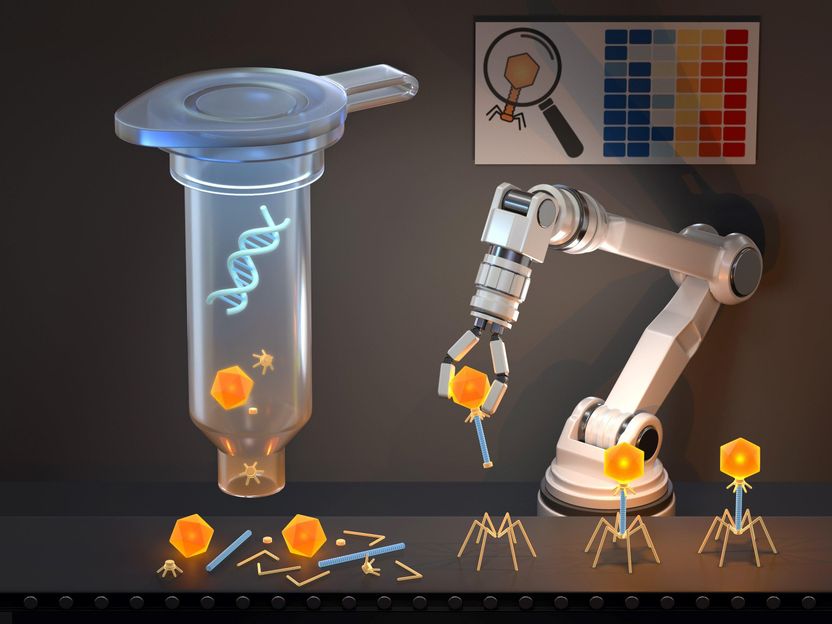

Graphical Abstract

Barth van Rossum / Clarafi

The World Health Organization (WHO) regards multi-resistant germs as among the largest threats to health. In the European Union alone, 33,000 people die each year as the result of bacterial infections which cannot be treated with antibiotics. Alternative treatments or drugs are therefore urgently needed.

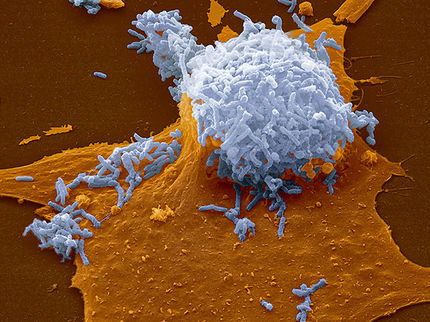

Bacteriophages, the natural enemies of bacteria, are one promising solution. There are millions of different types of these viruses on earth, each of which specializes in certain bacteria. In nature, the viruses use the bacteria to reproduce; they insert their DNA into the bacteria, where the viruses quickly multiply. Ultimately they kill off the cell and move on to infect new cells. Bacteriophages work as a specific antibiotic by attacking and destroying a particular type of bacterium.

Viruses for health

"Bacteriophages offer an enormous potential for the highly effective, personalized therapy of infectious bacterial diseases," observes Gil Westmeyer, Professor of Neurobiological Engineering at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and Director of the Institute for Synthetic Biomedicine at Helmholtz Munich. "However, in the past, it wasn't possible to produce bacteriophages in a targeted, reproducible, safe and efficient manner – although these are exactly the decisive criteria for the successful production of pharmaceuticals."

Now the research team has developed a new controlled production method to create bacteriophages for therapeutic use. The basis for this technology was established by a group of students at TUM and Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), who earned an award in the 2018 International Genetically Engineered Machine competition (iGEM). This group then gave rise to the spin-off Invitris, which is currently developing a platform technology for phage-based medications.

The cornerstone of the new technology, which is already in the patent application process and is now being used in new research at TUM, is a special nutrient solution in which the bacteriophages form and reproduce. The nutrient solution consists of an E. coli extract and contains no viable cells; this is a fundamental difference from previous bacteriophage production methods, which traditionally used cell cultures with potentially infectious strains of bacteria.

In the TUM labs, the Munich team has now been able to demonstrate targeted production of bacteriophages in the cell-free nutrient solution: The only component needed is the genome – the plain DNA – of the desired viruses. The genome contains the entire blueprint for the formation of the bacteriophages. When the DNA is injected into the nutrient solution containing the molecular components and enzymes of the E. coli bacterium, the proteins assemble according to the blueprint: Thousands of identical copies are generated in just a few seconds. "This production method is not only fast and efficient, but it's also very clean – the process eliminates contamination by bacterial toxins or other bacteriophages, which are a possible complications in cell cultures," says Westmeyer.

Personalized antibiotics

But is the new cell-free nutrient solution actually suited for the production of bacteriophages that could be used in individual therapies? The researchers put the idea to the test together with the Bundeswehr Hospital Berlin: Using a bacterial sample from a patient who was suffering from an antibiotic-resistant skin infection, the Munich team screened for a promising, novel bacteriophage and isolated its DNA. The phage was then produced in the cell-free nutrient solution and finally used to successfully combat the multi-resistant bacteria.

A genetic archive for emergencies

"Our studies prove the feasibility of a cell-free method for producing effective bacteriophages for personalized medicine that can also be used to address multi-resistant germ infections," says Westmeyer. He adds that in the future the methodology could ideally be used together with a genetic archive that would store the DNA of the relevant bacteriophages. Whenever necessary, this archive could be used to quickly produce complete bacteriophages in the nutrient solution, test their efficacy and then to apply the phages in the appropriate combinations, Westmeyer says, adding that although this work is still at the basic research stage, the method nevertheless has potential for clinical trials.

Original publication

Quirin Emslander, Kilian Vogele, Peter Braun, Jana Stender, Christian Willy, Markus Joppich, Jens A. Hammerl, Miriam Abele, Chen Meng, Andreas Pichlmair, Christina Ludwig, Joachim J. Bugert, Friedrich C. Simmel, Gil G. Westmeyer; "Cell-free production of personalized therapeutic phages targeting multidrug-resistant bacteria."; Cell Chemical Biology (2022).