Targeted drug shows clinical benefits in melanoma brain metastases

Advertisement

A new cancer drug, dabrafenib, may add vital months to the lives of patients whose melanoma has spread to their brains, an early study has shown. The results represent a promising step forward in the treatment of this potentially deadly cancer, commented Prof Wolfgang Wick, member of the ESMO Central Nervous System Tumors Faculty group.

“Although the trial is uncontrolled and hence not definitive, it is the first study to show relevant biological and clinical effects of a targeted therapy in a defined group of brain metastasis patients,” said Prof Wick, Director of the Department of Neuro-oncology at Germany’s National Centre for Tumor Diseases and chair of the EORTC Brain tumors group.

“The results offer some hope for advanced melanoma patients. Their disease is increasingly well understood, and pathway inhibitors like BRAF-inhibiting dabrafenib may improve their situation and prolong their life,” he said.

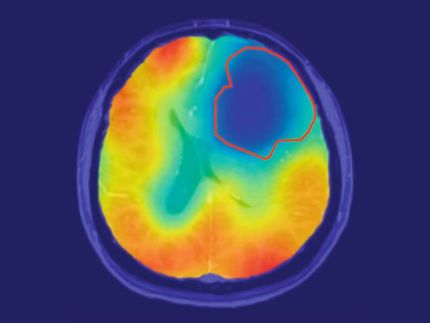

There is no doubt that better treatments are urgently needed for melanoma brain metastases, noted Prof Wick. ”Overall there is a dismal prognosis for stage IV melanoma patients as soon as the brain is involved. Patients not only experience epileptic seizures but also permanent neurological and neuropsychological deficits.”

The most common therapeutic modality used in 2012 for multiple brain metastases is whole-brain radiotherapy with potentially harmful psychological and neuro-cognitive effects, he said.

The new trial, published in The Lancet, focused on dabrafenib, an oral drug designed to inhibit a cancer-related protein called B-Raf, which is involved in the growth of cells. The drug specifically targets tumors in which the gene that makes this protein, called BRAF, has been mutated. Preliminary results were presented at the ESMO 2010 Congress in Milan.

“Approximately 50% of melanoma patients have BRAF mutations,” explained Dr Georgina Long, from the Melanoma Institute Australia and Westmead Hospital in Sydney, who is co-lead author of the study with Dr Gerald Falchook from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA.

They treated 184 patients with the drug in a Phase I trial, which is the earliest step of the drug development process in humans.

The most exciting results came from a subset of 10 patients whose tumors had spread to their brains. “Many melanoma patients develop brain metastases, which are very difficult to treat with standard therapies and are a common cause of death,” Dr Falchook explained. “Almost one in four melanoma patients already have brain metastases when they are first diagnosed with metastatic melanoma, and nearly another fourth develop them later.”

None of the patients whose cancer had spread to their brains had received prior treatment for their brain involvement. When the researchers gave them 150 mg of dabrafenib twice daily, four experienced a complete disappearance of their brain metastases. Another five patients saw their brain metastases shrink, and one had stable disease where the brain tumors stayed the same size.

“I don’t think there is a single other systemic agent that is as active in the brain,” Dr Long said. “The results in the brain were remarkable.”

The researchers are not sure why the drug was so effective in the brain where other drugs have failed. Trials are underway to try to clarify the mechanism. “The big message is that the brain with this drug is just like another organ,” Dr Long said. “If you are going to respond in your lung and liver you tend to respond in your brain as well.”

Unfortunately, for most of the patients in the trial with brain metastases, the response to the drug was limited to several months. Nine of the patients have since seen their disease progress, although not necessarily in the brain.

Nevertheless, these results are very promising and may represent an extension of life expectancy for patients with melanoma that has spread to the brain, Dr Long said.

“Normally, patients diagnosed with brain metastases from melanoma can expect to survive for 4 months from the point of diagnosis,” she said. “With this drug, these patients had no progression of their disease for a median of 4.2 months. Without treatment, many of them might already have died at that point.”

Two of the 10 brain metastasis patients who received the drug survived for more than 12 months. One was still alive and receiving the drug at 19 months.

Prof Wick said the results were a good step forward in the treatment of melanoma metastases. “The data show that it is possible to not only control but really influence brain metastases from melanoma with BRAF mutations. The data support the paradigm that brain metastases should be treated like any other solid metastases,” he said.

Further research will be needed to focus on strategies for using dabrafenib with other drugs, and in defining the right time-point for this therapy in the treatment of stage IV melanoma with BRAF mutations, Prof Wick said.

“Given the great response rates but the rather uniform and relatively fast failure, the pathway blocked seems to be of great relevance but also easy to circumvent for the treated tumors. Mechanisms for secondary resistance need to be investigated and understood in order to further build on these findings.”

The data on response and overall survival benefit need to be confirmed in controlled trials, Prof Wick added. “It would also be great to see to what extent a previously non-brain-irradiated patient benefits in terms of preservation of neurocognitive functioning over standard-of-care radiotherapy.”