Scientists uncover strong support for once-marginalized theory on Parkinson's disease

Advertisement

University of California, San Diego scientists have used powerful computational tools and laboratory tests to discover new support for a once-marginalized theory about the underlying cause of Parkinson's disease.

The new results conflict with an older theory that insoluble intracellular fibrils called amyloids cause Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Instead, the new findings provide a step-by-step explanation of how a "protein-run-amok" aggregates within the membranes of neurons and punctures holes in them to cause the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

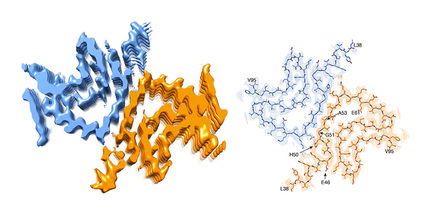

The discovery, published in FEBS Journal, describes how α-synuclein (a-syn), can turn against us, particularly as we age. Modeling results explain how α-syn monomers penetrate cell membranes, become coiled and aggregate in a matter of nanoseconds into dangerous ring structures that spell trouble for neurons.

"The main point is that we think we can create drugs to give us an anti-Parkinson's effect by slowing the formation and growth of these ring structures," said Igor Tsigelny, lead author of the study and a research scientist at the San Diego Supercomputer Center and Department of Neurosciences, both at UC San Diego.

Familial Parkinson's disease is caused in many cases by a limited number of protein mutations. One of the most toxic is A53T. Tsigelny's team showed that the mutant form of α-syn not only penetrates neuronal membranes faster than normal α-syn, but the mutant protein also accelerates ring formation.

"The most dangerous assault on the neurons of Parkinson's patients appears to be the relatively small α-syn ring structures themselves," said Tsigelny. "It was once heretical to suggest that these ring structures, rather than long fibrils found in neurons of people having Parkinson's disease, were responsible for the symptoms of the disease; however, the ring theory is becoming more and more accepted for this neurodegenerative disease and others such as Alzheimer's disease. Our results support this shift in thinking."

The modeling results also are consistent with the electron microscopy images of neurons in Parkinson's disease patients; the damaged neurons are riddled with ring structures.

Wasting no time, the modeling discoveries have spawned an intense hunt at UC San Diego for drug candidates that block ring formation in neuron membranes. The sophisticated modeling required involves a complex realm of science at the intersection of chemistry, physics, and statistical probabilities. A kaleidoscope of interacting forces in this realm makes α-syn proteins bump and tremble like they're in an earthquake, coil and uncoil, and join together in pairs or larger groups of inventive ballroom dancers.

The modeling is creating a much better understanding of the mysterious a-syn protein itself, according to Tsigelny. A few years ago it was shown to accumulate in the central nervous system of patients with Parkinson's disease and a related disorder called dementia with Lewy bodies.

The new modeling study has revealed precisely how two α-syn proteins insert their molecular toes into the membrane of a neuron, wiggle into it in only a few nanoseconds and immediately join together as a pair. The pair isn't itself toxic; however, when more α-syn proteins join the dance, a key threshold is eventually crossed; polymerization accelerates into a ring structure that perforates the membrane, damaging the cell.

Tsigelny said many ring structures may be required to actually kill neurons, which are known for their durability. The nerve cells may be able to repair dozens of ring-induced perforations, keeping pace with a-syn assault. But at some point, the rate of perforations surpasses the ability of neurons to repair them. As a result, symptoms of Parkinson's disease gradually appear and worsen.

"We think we can create a drug that stops the α-syn polymerization at the point of non-propagating dimers," Tsigelny said. "By interrupting the polymerization at this crucial step, we may be able to slow the disease significantly."