Leukemia cells activate cellular recycling program

The findings open up new therapeutic options for the future

Advertisement

To speed up their growth, leukemia cells typically activate the recycling of cellular structures – enabling them to dispose of defective components and better supply themselves with building materials. Researchers at Goethe University Frankfurt have now shown that leukemia cells with a very common mutation activate specific genes that are important for this recycling process. Their findings, published in the journal Cell Reports, open up new therapeutic options for the future.

In a recent study, scientists led by Professor Stefan Müller from Goethe University’s Institute of Biochemistry II investigated a specific form of blood cancer known as acute myeloid leukemia, or AML. The disease mainly occurs in adulthood and often ends up being fatal for older patients. In about a third of AML patients, the cancer cells’ genetic material has a characteristic mutation that affects the so-called NPM1 gene, which contains the building instructions for a protein of the same name.

While it was already known that the mutated NPM1 variant (abbreviated as NPM1c) is an important factor in the development of leukemia, "together with an interdisciplinary team consisting of various Goethe University research groups, we have now discovered a new way in which the NPM1c gene variant does this," Müller explains. According to this, the altered protein intervenes in autophagy, an important cell process that consists of a metabolic pathway through which the cell recycles its own structures. On the one hand, this "self-digestion" serves to remove defective molecules. "On the other, it also enables the cell to meet its need for important building blocks, including in the event of a nutrient deficiency or increased cell proliferation, which is characteristic of cancer cells," explains PhD student Hannah Mende, the study’s first author.

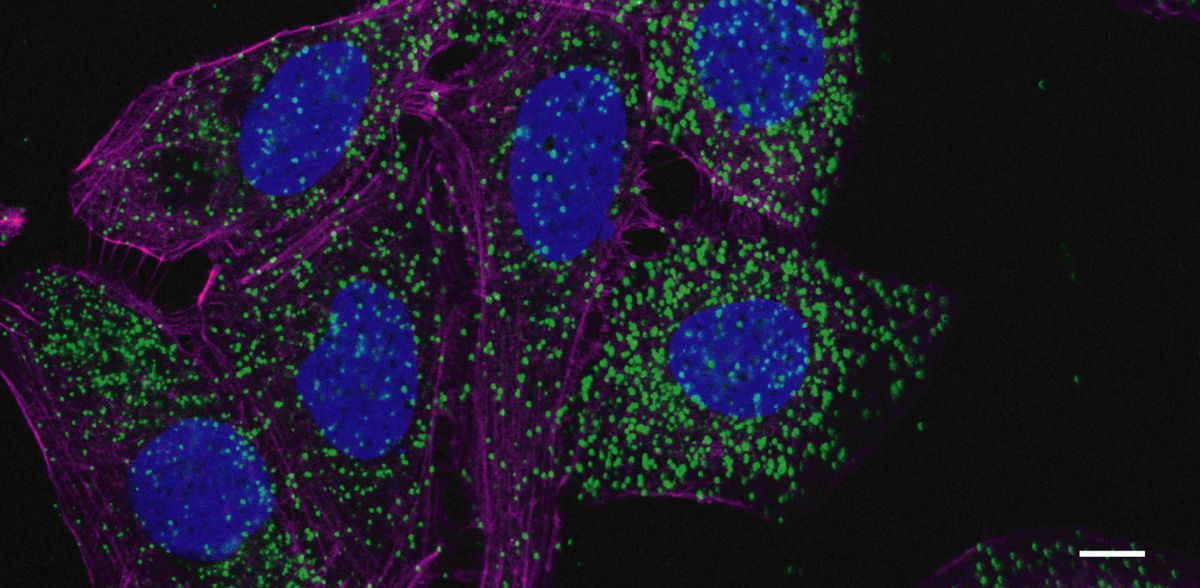

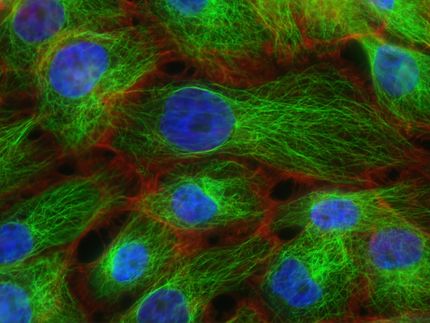

During autophagy, the cell initially produces a kind of waste bag, the autophagosome, into which it packs those cellular components that are to be broken down and recycled if necessary. This waste bag is then transported to the cell's recycling center, the so-called lysosome, where its contents are broken down with the help of acid and enzymes. From here, the building blocks are then released into the cell, where they can be reused. "We have now been able to show that NPM1c promotes the production of both autophagosomes as well as lysosomes," says Müller.

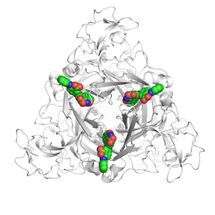

The researchers have also provided an answer to the question of how NPM1c imparts these effects: It binds to a central regulator of the autophagosome-lysosome system called GABARAP, and thereby activates it. "Using computer simulations, we have shown that this binding of NPM1c and GABARAP has an atypical structure," explains study co-author Dr. Ramachandra M. Bhaskara, head of the Institute of Biochemistry II’s computational cell biology working group. Experimental structural biology data confirm the simulation’s results, based on which it may now be possible to develop active substances that specifically influence the binding of NPM1c to GABARAP and thus combat the growth of leukemia cells.

Original publication

Hannah Mende, Anshu Khatri, Carolin Lange, Sergio Alejandro Poveda-Cuevas, Georg Tascher, Adriana Covarrubias-Pinto, Frank Löhr, Sebastian E. Koschade, Ivan Dikic, Christian Münch, Anja Bremm, Lorenzo Brunetti, Christian H. Brandts, Hannah Uckelmann, Volker Dötsch, Vladimir V. Rogov, Ramachandra M. Bhaskara, Stefan Müller; "An atypical GABARAP binding module drives the pro-autophagic potential of the AML-associated NPM1c variant"; Cell Reports, Volume 42