Knights in golden armor to the rescue: Novel encapsulation of vitamin B3

Advertisement

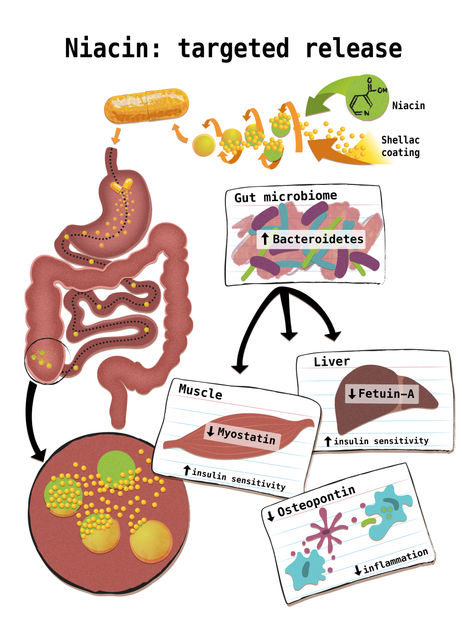

Vitamin B3, also known as niacin, can promote the growth of "good bacteria" in the gut, which creates health-boosting effects for the whole body. For this to take place though, relatively large amounts of niacin need to reach as far as the large intestine. The stomach and small intestine prevent this from happening, however, because they almost completely absorb the substance on its way through the digestive system. Researchers from the Cluster of Excellence "Inflammation at Interfaces" have now developed a novel transport casing for the niacin. They coated the substance in a protective covering, so that the niacin is not released until it arrives in the large intestine, the place where it should take effect. These new findings, for which a worldwide patent application is pending, have now been published in the specialist journal Diabetes Care.

The vitamin niacin is covered with a protective layer composed of shellac. Packed inside a gelatin capsule, it can easily be consumed. The capsule already dissolves within the stomach, however, the protected niacin reaches the intestine. Here, it has provable positive influence on the whole organism: It promotes the existence of Bacteroidetes, a very common species of bacteria inside the digestive tract, which have important health effects on the metabolism. Moreover, the recent study showed that encapsulated niacin can reduce first occurring symptoms of insulin malfunction as well as inflammation within the metabolism.

Graphic/copyright: Holly McKelvey/Cluster of Excellence "Inflammation at Interfaces"

Niacin is a vitamin from the so-called B-complex class. It is stored in the liver, and is important for a number of metabolic processes in the body. As early as 2012, researchers under the direction of cluster member Professor Philip Rosenstiel showed that niacin has an anti-inflammatory effect in the large intestine. But it is difficult to transport the substance to the large intestine in sufficient quantities, since it is usually absorbed into the blood when it passes through the stomach and small intestine. In addition, a high intake of non-encapsulated niacin can trigger a so-called flush in some people, which causes a red face and possibly a burning or itching sensation on the skin. If someone takes niacin in high doses over longer periods, this can also have harmful effects, such as damage to the liver. Therefore, in an interdisciplinary project between Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Medicine (Director: Professor Matthias Laudes) at the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein (UKSH) and the Food Technology department (Director: Professor Karin Schwarz) at Kiel University, the researchers developed a kind of armor for the niacin.

In so doing, the scientists had to find a substance permitted for use as “packaging material” for food. "Because this is the only way the product can later be brought to the market as a foodstuff or food supplement," explained Eva-Maria Theismann from the Food Technology department, one of the lead authors. They found a suitable packaging procedure, and coated small vitamin pellets using a spraying method. "Coating is the heart of microencapsulation. We have also applied for a patent for this process. We developed a special formulation, which specifically releases the niacin in the desired section of the intestine." To achieve this, the researchers made use of the different pH values occurring in the body. The encapsulated pellets do not dissolve in the stomach and small intestine, but they do in the large intestine.

In a pilot study using healthy volunteers, the scientists tested if and when the encapsulated niacin was absorbed into the blood. They were able to demonstrate that the newly-developed method only releases the niacin in the large intestine, and that the blood levels hardly increased. "We are delighted with how well our process works," said Dr Daniela Fangmann, nutrition scientist in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Medicine at the UKSH, another lead author of the study. "With our development, we are able to deliver the niacin specifically to the area of the body where it has the greatest benefit." In order to facilitate easy dosage, the niacin pellets are packaged in gelatin capsules, as used with other dietary supplements.

The first results show that the niacin remains in its protective coating until released in the large intestine. As such, the vitamin B3 showed a strong influence on so-called Bacteroidetes. This is a very common type of bacteria in the digestive tract, which has an important and health-promoting effect on the metabolism. Head of the study, Professor Matthias Laudes added: "In our pilot study, we were able to demonstrate that the encapsulated niacin could alleviate the initial signs of insulin disorders and inflammation in the metabolism. Now we need to check whether our patent is suitable for preventive treatment in humans, for example for those who have a significantly increased risk of developing diabetes." In parallel, members of the Cluster of Excellence "Inflammation at Interfaces", under the leadership of the cluster spokesperson Professor Stefan Schreiber, are also investigating whether the patented procedure may be suitable for treating chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, because the anti-inflammatory effect of the substance in the large intestine has already been proven in scientific studies.

Original publication

Fangmann, D, Theismann, EM, Türk, K, Schulte, DM, Relling, I, Hartmann, K, Keppler, JK, Knipp, JR, Rehman, A, Heinsen, FA, Franke, A, Lenk, L, Freitag-Wolf, S, Appel, E, Gorb, S, Brenner, C, Seegert, D, Waetzig, GH, Rosenstiel, P, Schreiber, S, Schwarz, K und Laudes, M; "Targeted microbiome intervention by microencapsulated delayed-release niacin beneficially affects insulin sensitivity in humans"; Diabetes Care; 2017