Antibiotics take toll on beneficial microbes in gut

In mice, recovery of microbiota that aid immune system is slow, incomplete

Advertisement

It's common knowledge that a protective navy of bacteria normally floats in our intestinal tracts. antibiotics at least temporarily disturb the normal balance. But it's unclear which antibiotics are the most disruptive, and if the full array of "good bacteria" return promptly or remain altered for some time.

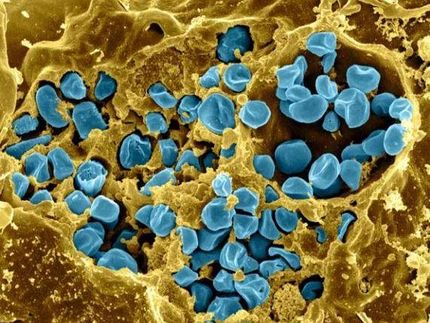

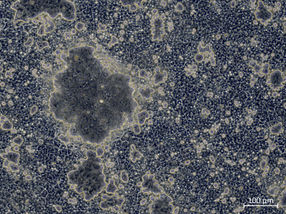

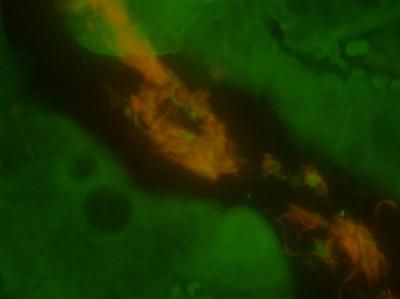

Gastrointestinal microbiota live in close contact with the intestinal mucosa.

University of Michigan

In studies in mice, University of Michigan scientists have shown for the first time that two different types of antibiotics can cause moderate to wide-ranging changes in the ranks of these helpful guardians in the gut. In the case of one of the antibiotics, the armada of "good bacteria" did not recover its former diversity even many weeks after a course of antibiotics was over.

The findings could eventually lead to better choices of antibiotics to minimize side effects of diarrhea, especially in vulnerable patients. They could also aid in understanding and treating inflammatory bowel disease and Clostridium difficile , a growing and serious infection problem for hospitals.

Normally, a set of thousands of different kinds of microbes lives in the gut – a distinctive mix for each person, and thought to be passed on from mother to baby. The microbes, including many different bacteria, aid digestion and nutrition, appear to help maintain a healthy immune system, and keep order when harmful microbes invade.

The study results suggest that unless medical research discovers how to protect or revitalize the gut microbial community, "we may be doing long-term damage to our close friends," says Vincent B. Young, M.D., Ph.D., , assistant professor in the departments of internal medicine and microbiology and immunology at the U-M Medical School.

Young and his colleagues used a culture-independent technique, using sequence analysis of 16S rRNA-encoding gene libraries, to profile the bacterial communities in the gut. It allows them to look for many more kinds of microbes than was possible with more limited methods. The result is a much more complete picture of the diversity of microbes in the gut.

Original publication: Dionysios A. Antonopoulos, Susan M. Huse, Mitchell L. Sogin, Hilary G. Morrison, Woods Hole, Thomas M. Schmidt; Infection and Immunity 2009, Vol. 77, Issue 6.