Nature-inspired technology creates engineered antibodies to fight specific diseases

Advertisement

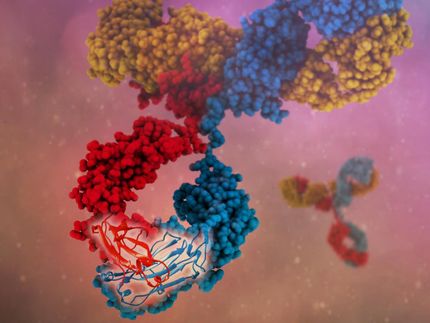

When viruses and bacteria invade the body, the immune system generates protective proteins called antibodies that bind to and destroy the invading pathogens. A new genetic-engineering technique invented by Cornell researcher Matthew DeLisa could pave the way for creating and cataloging disease-specific antibodies in the lab. The technique could revolutionize antibody-based drugs for such illnesses as Alzheimer's and cancer.

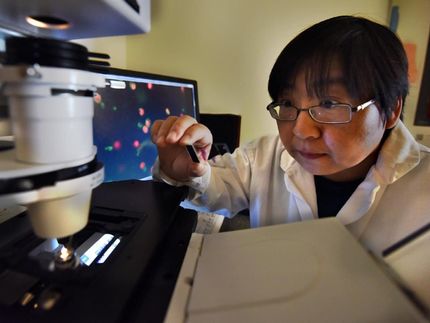

The method, which involves the efficient "readout" of protein-to-protein interactions within cells, was reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science and is co-authored by Dujduan Waraho, a former graduate student. DeLisa, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, and his collaborators have long studied a mechanism, called the twin-arginine translocation pathway, in bacteria and plant cells that allows completely folded proteins to diffuse across tightly sealed lipid membranes and infiltrate other parts of the cell.

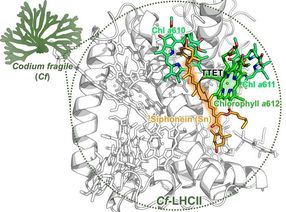

Only a protein carrying a so-called signal peptide can get across the membrane. Sometimes, though, another protein interacts with and latches onto the protein with the signal peptide, essentially going along for the ride - in fact, this phenomenon is called hitchhiker transport.

Inspired by this natural process, the researchers have developed a technology that can screen for antibody-antigen matches by taking a fragment of an antibody and attaching a signal peptide to it. They then attached to the antigen a reporter - in this case an enzyme, beta-lactamase - which causes resistance to such antibiotics as penicillin. The genes encoding these engineered proteins were placed into E. coli cells, enabling these cells to express the genes and make the proteins.

If the cells became resistant to penicillin, the researchers knew the antibody was a match for the antigen, because the proteins must have interacted in order to pass through the membrane and into the part of the cell that contained the antibiotic. Otherwise, the beta-lactamase could not have spread and caused penicillin resistance.

This method allows scientists to quickly look at antibody-antigen interactions and to screen antibody "libraries" to identify matches for specific antigens. Armed with this information, scientists can then engineer and manufacture antibodies in the laboratory.

"You can put any antigen you want into our system, and for the most part, it allows you to find antibodies that recognize the antigen," DeLisa said.

DeLisa has worked with Cornell Center for Technology, Enterprise and Commercialization (CCTEC) to obtain a patent on the technique. Meanwhile, the Ithaca-based biotechnology company Vybion Inc. has negotiated an exclusive license with CCTEC to use the technology, which it is using for in-house drug development and other related projects.

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous