Mayo Clinic researchers discover drug can prevent colon cancer development in mice

Advertisement

Researchers at the Mayo Clinic campus in Florida have found that a drug now being tested to treat a range of human cancers significantly inhibited colon cancer development in mice. Because the agent appears to have minimal side effects, it may represent an effective chemopreventive treatment in people at high risk for colon cancer, the investigators say.

Their study, published in Cancer Research, found that use of the agent, enzastaurin, significantly reduced development of cancerous colon tumors in treated animals. Furthermore, the tumors that did develop in the mice were of a lower grade, which meant they were less advanced and aggressive than the tumors seen in animals not given the drug.

"There is need for an agent that has a proven ability to reduce colon cancer risk, and this study suggests that enzastaurin could be uniquely effective," says the study's senior investigator, Nicole Murray, Ph.D., of the Department of Cancer Biology.

Individuals at high risk for colon cancer often develop numerous precancerous colon polyps, which must be periodically removed during a colonoscopy, Dr. Murray says. The laboratories of Dr. Murray, and her collaborator and co-author, Alan Fields, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Cancer Biology, focus on characterizing the genes involved in different stages of colon carcinogenesis. They have zeroed in on the protein kinase C (PKC) family of enzymes as major players in cancer development and progression, but it has taken them years to understand the different roles of each type of PKC molecule or "isozyme."

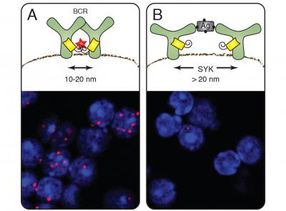

Using transgenic mice in which different PKC genes have been selectively deleted or silenced, the researchers have determined pivotal roles for two of the major isozymes. In Cancer Research, they reported that PKC-beta is necessary for initiation of colon cancer in mice exposed to a carcinogen. "These mice develop colon tumors similar to tumors found in humans, but mice without a PKC-beta gene do not," Dr. Murray says.

In that study, they also demonstrated that a different PKC isozyme known as PKC iota-lambda is involved in progression of colon cancer. If the PKC iota-lambda gene is deleted in mice models that mimic the type of cancer seen in people with an inherited form of colon cancer, the cancer doesn't progress at such a rapid rate, Dr. Murray says. "But in those same mice, if we knock out the PKC-beta gene, there is no effect," she says.

"This tells us that over-expression of PKC-beta and PKC iota-lambda serve distinct, nonoverlapping roles in colon carcinogenesis, conspiring to drive initiation and progression of colon carcinogenesis, respectively," Dr. Murray says.

Those findings suggested that targeting these different PKC isozymes could have distinct cancer treatment benefits. Targeting PKC-beta in colon cells could help prevent initial cancer development, and inhibiting PKC iota-lambda might help stop progression of cancer that has already developed, she says.