External brain stimulation temporarily improves motor symptoms in people with Parkinson's

Advertisement

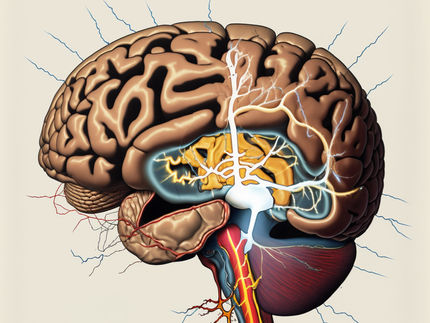

People with Parkinson's disease (PD) tend to slow down and decrease the intensity of their movements even though many retain the ability to move more quickly and forcefully. Now, in proof-of-concept experiments with "joysticks" that measure force, a team of Johns Hopkins scientists report evidence that the slowdown likely arises from the brain's "cost/benefit analysis," which gets skewed by the loss of dopamine in people with PD.

In addition, their study with a small group of 20 patients with PD demonstrated that stimulation of the cortex of the brain using external electrodes corrected some of the distortion and temporarily improved some patients' motor symptoms. PD affects up to 1 million Americans.

"The loss of dopamine associated with Parkinson's disease makes the effort required to move the affected side of the body seem greater, so the brain is less willing to use that arm to complete tasks," says Reza Shadmehr, Ph.D., professor of biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Our study suggests that direct current stimulation can compensate somewhat for the loss of dopamine by decreasing the effort the brain has to put into getting its motor neurons to fire," adds Shadmehr.

According to the researchers, their experiments stemmed from the knowledge that dopamine, the chemical released throughout the cortex of the brain by specialized neurons, is known to make animals more likely to exert effort to achieve a reward. In Parkinson's, dopamine neurons generally die on one side of the brain, affecting the ability of the patient to exert effort with the opposite side of the body. In urgent situations as simple as preventing a ball from falling off a table, for example, people with PD can often still make rapid, intense movements with their affected arm, but it seems as though the brain's "cost assessment" for making everyday movements is abnormally high.

To test this hypothesis, Shadmehr and his team first designed an experiment to measure how much force a patient's brain was willing to "assign" to each arm. In their first experiment, participants, all right-handed, included 15 healthy volunteers and 15 with PD, ages 50 to 75, who had had Parkinson's for two to 20 years and were receiving medication to control their symptoms, such as tremors, muscle rigidity and lack of balance.

Shadmehr's team says the difference was not due to a lack of strength in the affected arm of the patients with PD, because the team also tested each arm's ability to apply force in every direction and found that the patients' strength was comparable to that of healthy individuals.

What did stand out, the researchers say, was how direction-dependent the outcomes were. For example, when a patient was asked to move the cursor to the 3 o'clock position on the screen, she might entirely favor her left (unaffected) arm. However, when the patient was asked to move the cursor to the 12 o'clock position, she might share the effort equally between her two arms. In addition, the researchers noticed that patients avoided using their affected arm particularly in the directions in which they exhibited a greater amount of variability, or "noise," when generating force. That is, the increased effort appeared associated with a poorer ability to control the generation of force.