Unique nasal microbiome

Advertisement

Study shows individual differences in the immune response of the nose. Researchers at the University of Tübingen provide new insights into the specific antibody response of the body's own immunoglobulin A. The results help to better understand the body's immune response.

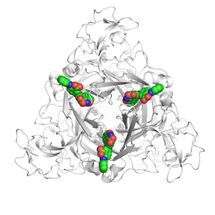

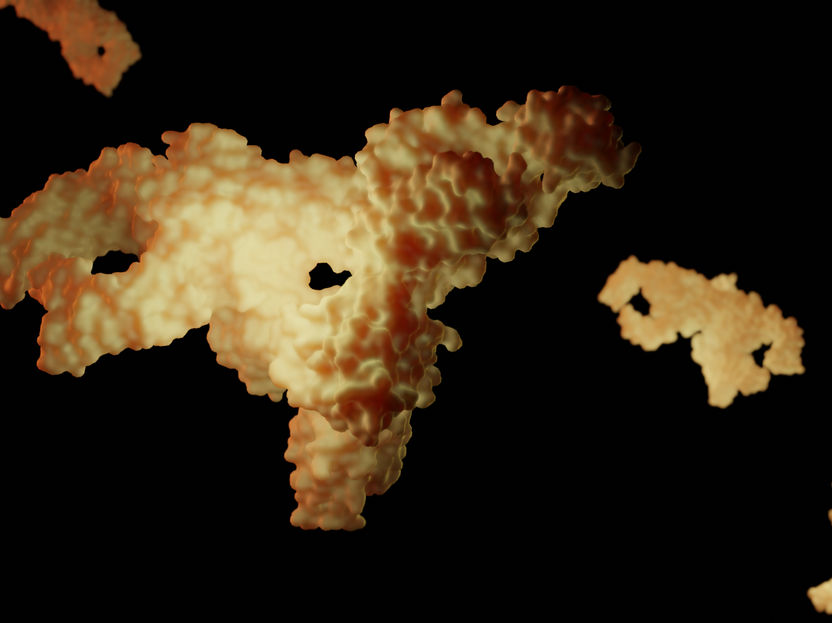

The secretory antibody immunoglobulin A (sIgA), which occurs naturally in body fluids of the human body. In this study, its reactivity with bacteria of the nasal microbiome was investigated. Exemplary representation of sIgA 6LX3 The secretory antibody immunoglobulin A (sIgA), which occurs naturally in body fluids of the human body. In this study, its reactivity with bacteria of the nasal microbiome was investigated. Exemplary representation of sIgA 6LX3

© Leon Kokkoliadis / Universität Tübingen.

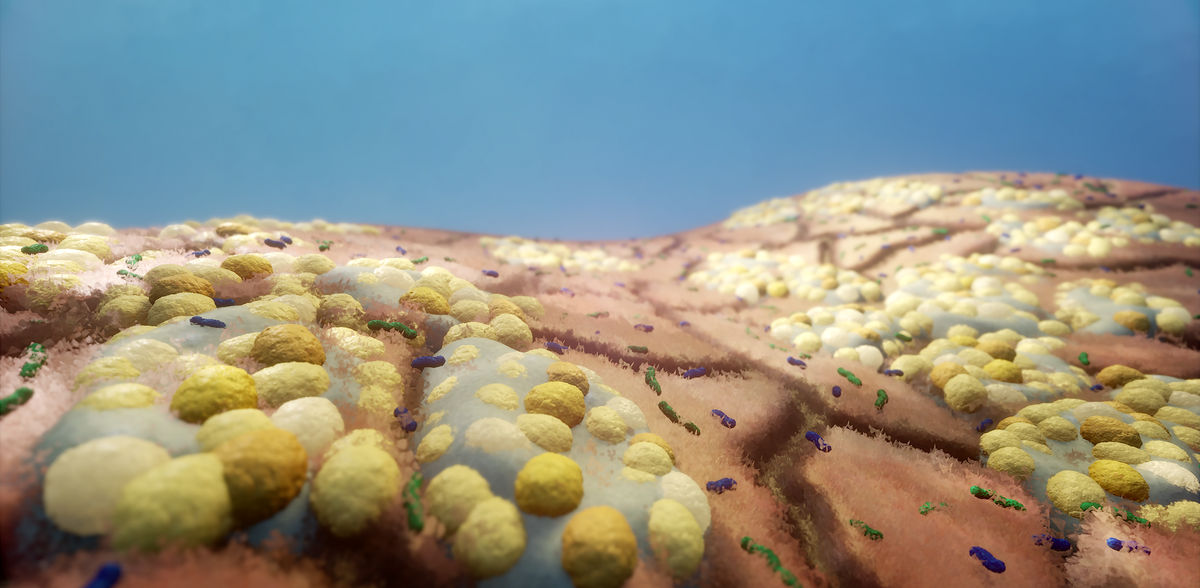

A recent study published in the journal Microbiome sheds new light on the complex interplay between the human immune system and the microorganisms that colonize our nose. Local immune responses in the nose are most likely a determining factor for infections caused by respiratory pathogens. Nevertheless, this part of the immune system has remained largely unexplored. The study now focused on the endogenous antibody secretory immunoglobulin A, or sIgA for short. This antibody is crucial to the body's immune response because it is actively involved in neutralizing pathogens. sIgA is abundant in our nasal secretions, saliva, sweat, intestinal fluid, tears and breast milk.

Strong individual differences in immune response

The study was able to show that the amounts of IgA in different people can differ by more than a hundredfold. For many bacteria, the IgA score, which measures the reactivity of the antibody to a particular bacterial species, was also highly variable. Individuals showed a clear IgA response to certain microorganisms, while others did not. This suggests that each individual's nasal mucosa reacts differently to the microbes in their environment, which may explain different susceptibilities to infection.

Researchers from the Cluster of Excellence "Controlling Microbes to Fight Infections" (CMFI) at the University of Tübingen, Germany, have observed a highly individualized response of sIgA to the microbes that live in the human nose. The strength of the immune response could depend on the particular genetics of the host, its immune system and local conditions. This discovery underscores the unique nature of the human immune response.

Regulating the nasal microbiome to fight infection

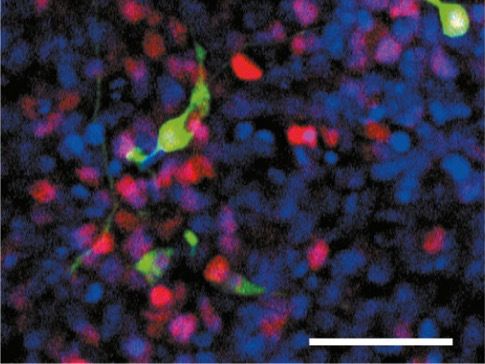

One focus of the study was to observe how sIgA and the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus interact. S. aureus is a bacterium that occurs naturally in the nose of many people and is initially harmless. However, S. aureus can develop into a pathogenic variant and cause infections. In particular, the reaction of the antibiotic-resistant variant MRSA, known as the hospital germ and feared for dangerous and difficult-to-treat infections, has been studied. Interestingly, sIgA appears to have a specific interaction with a protein called SpA, which sits on the surface of S. aureus. This suggests potential new therapeutic approaches in which this interaction could potentially be manipulated to enhance the immune response or more effectively neutralize the pathogenic bacterium.

"We are beginning to understand the processes in our microbiomes better and better. The interactions of the antibody sIgA with the nasal microbiome give us a powerful demonstration of how these microbial systems regulate themselves - and could be regulated. We have a huge potential here for future treatment methods," says Rob van Dalen, postdoctoral researcher in the Cluster of Excellence CMFI and first author of the study.

Nasal swabs from about 50 healthy individuals were analyzed. This showed that the amount of sIgA in the nasal mucosa has a direct influence on the number of bacteria living there. Individuals with higher levels of sIgA appear to be colonized by fewer bacteria, suggesting that this antibody plays a role in regulating the microbial population and thus also prevents the growth of harmful bacteria. sIgA could lend itself to new treatments.

But even though the results are promising, it could be a long time before new therapeutic methods are developed.

"We often talk about 'bench to bedside,' or translating research results obtained at the lab bench into the clinic. But it is often a long way before this translation succeeds. We need the right investors and partners who are willing to travel this road with us," says study leader Andreas Peschel, Professor of Microbiology at the University of Tübingen and spokesman for the CMFI Cluster of Excellence.

The research results now presented expand the understanding of how the immune system and the microbiome work together to maintain human health.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous