Intestinal inflammation: immune cells protect nerve cells after infection

New findings on the functions of the gut-brain axis

Advertisement

In the event of an infection in the gastrointestinal tract, part of the tissue becomes inflamed, and intestinal nerve cells die off. Among other things, this loss in turn often leads to a restriction of the gastrointestinal motility, which is essential for a healthy digestion. In many cases, this is also followed by additional diseases, such as the so-called irritable bowel syndrome. The reason for the nerve cells dying off has previously been unclear. An international research team involving Professor Philip Rosenstiel, Director at the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology (IKMB) at Kiel University (CAU), has now succeeded in describing the mechanism that leads to the death of the nerve cells. Specific immune cells in the gut appear to protect the nerve cells, as the team was able to demonstrate in their current research. The scientists, led by Daniel Mucida, Associate Professor at The Rockefeller University in New York, recently published their results in the renowned scientific journal Cell.

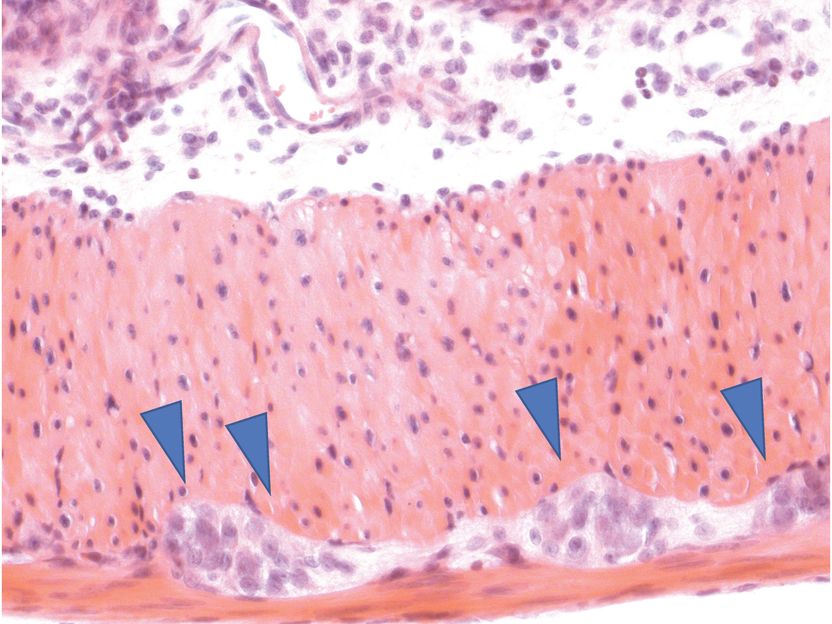

The gut is permeated by nerve cells (embedded in muscle tissue, marked by blue arrows). They form a separate nervous system that for example regulates gastrointestinal motility, which is essential for a healthy digestion.

P. Rosenstiel, IKMB Uni Kiel

The human gastrointestinal tract is permeated by nerve cells, which form a separate enteric nervous system. This controls digestion largely independently, for example by regulating the gastrointestinal motility. Previous studies have shown that the immune system in the gut also plays an important role. For example, specific immune cells regulate the activity of the nerve cells in healthy individuals. These interactions between nerve and immune cells are disrupted by diseases such as chronic inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome.

“The research shows that immune cells are also important for the survival of nerve cells in the case of infections," said Professor Philip Rosenstiel, member of the Steering Committee of the Cluster of Excellence "Precision Medicine in Chronic Inflammation" (PMI). Accordingly, specific immune cells recognize the infection and limit the damage to nerve cells. The specific cells are so-called macrophages in the gastrointestinal muscular layer. These are scavenger cells which detect and destroy pathogens. In the event of an infection, these macrophages initiate a protection program, in which they produce certain substances that ultimately protect the nerve cells. In turn, this protection program is apparently dependent on the microorganisms living in the intestine, the so-called microbiome. If these are absent, or if their balance is disturbed, the nerve cells are also no longer protected.

"The so-called gut-brain axis, through which the intestinal microbiome, the intestinal cells and the central nervous system cooperate, is an important topic for the future at the Cluster of Excellence PMI. Because the gut-brain axis could lead to new approaches for treating chronic inflammation, and also neurological diseases," said Professor Rosenstiel. "The mechanism, which has now been discovered in cooperation with Daniel Mucida and his team from New York, through which the immune system in the gut protects nerve cells in the event of an infection, is an important building block in the exploration of the gut-brain axis. We want to expand on this at the Cluster of Excellence, and increase our research efforts in this area in future," added Rosenstiel.