How “good cholesterol” gets to do even more good work

Advertisement

In order for a tumour to grow, it needs cholesterol to build new cell walls. At the same time, the so-called “good” cholesterol or high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is regarded as a protective factor against cancer. Schrödinger fellow Raimund Bauer investigated the effect of HDL on tumours more closely and was able to show that a protective effect against cancer is strongly related to the structure of the HDL particles.

A healthy lifestyle prevents cancer. Current research shows how cholesterol interacts with cancer cells.

skeeze, pixabay.com, CC0

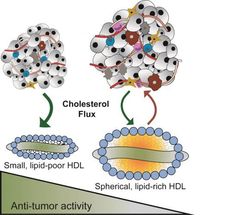

The high cholesterol-efflux capacity of small, discoidal HDL particles represents one important mechanism of how HDL interferes with tumor growth (left). In contrast, lipid-rich, spherical HDLs have reduced or even no anti-tumor activity (right).

Raimund Bauer

Being obese or seriously overweight are known risk factors for the development of cancer in the digestive system, especially in the colon and pancreas. “There are certainly multiple metabolic parameters that fall out of balance when you’re very much overweight. We know that fatty tissue not only stores fat but is also hormonally active. It is also known that blood lipid levels and the composition of blood lipids differ between metabolically fit and obese people,” says molecular biologist Raimund Bauer in describing the initial situation.

Found across all age groups, being overweight is caused by a diet that is highly processed, high in calories and rich in fats and carbohydrates, and this has been on the rise since the 1970s. According to current estimates, more than one in three people in the USA and about one in five in Europe are obese. With the support of an Erwin Schrödinger fellowship from the Austrian Science Fund FWF, Raimund Bauer’s research at the Hamburg University Hospital Eppendorf (UKE) focused on how HDL particles work in the microenvironment of tumours.

Structure determines function

Bauer did his research with mice which lack the main structural protein of HDL, apolipoprotein A-1 (APOA-1), and thus have strongly reduced HDL blood plasma levels. Normally, liver cells release the HDL structural protein APOA-1, lipid bodies attach to the protein and the assembled particle is then released into the bloodstream. One of the tasks of HDL is to remove excess cholesterol from the periphery of the body and transport it back to the liver for excretion. The tests initially focused on what effect HDL had on the formation of new blood vessels in tumours. While Bauer observed no direct effects, this gave rise to exciting projects with successful follow-up research (see publications). Subsequently, the researcher focused on the direct interaction of HDL with the tumour cells: “The structure of the HDL particles determines HDL’s function in the interaction with the tumour. We were able to show this by using HDL particles that have a strong cholesterol-removing effect,” explains Raimund Bauer, who is now continuing his research at the Institute of Medical Chemistry and Pathobiochemistry at the Medical University of Vienna.

What hard-working HDL particles look like

HDL cholesterol, which is generally rated as “good”, can become even better if the particles that remove cholesterol have a greater loading capacity. The “cholesterol-removing” effect was shown in reconstituted HDL particles, for which APOA-1 is biochemically combined with a phospholipid envelope. The researchers also found a protective effect in pancreatic cancer by taking the detour of simulating a viral infection of liver cells inducing them to produce an excess of APOA-1 structural proteins. These special HDL particles reduced the growth rate of tumours in mice and inhibited the cell division of pancreatic carcinoma in the cell culture.

“In and as of itself, a high HDL level does not necessarily slow tumour growth. However, the cholesterol-removing effect and the interaction with the receptors of tumour cells are central mechanisms by which HDL reduces tumour growth. If this is to be used in therapy, the structure and quantity must be specifically fine-tuned,” says Raimund Bauer by way of explaining the results of his investigations.

In the future, Bauer plans to use cell cultures to investigate the interaction of HDL fat particles with cancer cell receptors. It can be assumed that these lipoproteins are unable to perform their function in obese people, or perform it insufficiently. In cooperation with Jörg Heeren from the UKE in Hamburg, the metabolism expert hopes to find out how the fat particles of metabolically fit and heavily overweight people differ with regard to their tumour blocking activity. As a matter of principle, every individual can influence his or her blood lipid levels with a balanced diet and physical activity.