Study identifies the off switch for biofilm formation

Advertisement

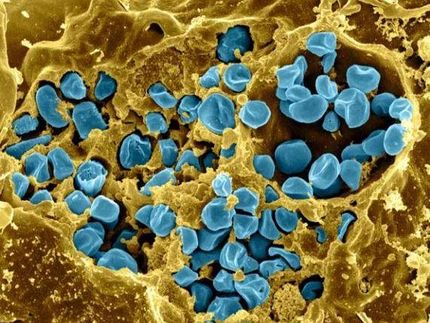

bacteria are best known as free-living single cells, but in reality their lives are much more complex. To survive in harsh environments, many species of bacteria will band together and form a biofilm -a collection of cells held together by a tough web of fibers that offers protection from all manner of threats, including antibiotics. biofilms are a huge problem in the health care industry. When disease-causing bacteria establish a biofilm on sensitive equipment, it can be impossible to sterilize the devices, raising rates of infection and necessitating expensive replacements. So researchers look for ways to break down the defenses of biofilms to prevent them from establishing a foothold.

Debra Weinstein, Sao-Mai Nguyen-Mau, and Vincent Lee

Now, a University of Maryland-led team has found an important link in the biofilm formation process: an enzyme that shuts down the signals that bacteria use to form a biofilm. The findings have far-reaching implications for the development of new treatments, and could one day help make biofilm-related complications a distant memory.

"Bacteria form biofilms because they sense a change in their environment. They do this by generating a signaling molecule, which binds to a receptor that turns on the response," said Mona Orr, the lead author of the study and a UMD biological sciences graduate student. "But you need a way to turn off the switch - to remove the signal when it's no longer needed. We've identified the enzyme that completes the process of turning off the switch."

The well-known switch that activates biofilm formation is a signaling molecule called Cyclic-di-GMP, also known as c-di-GMP. Many species of disease-causing bacteria use c-di-GMP to signal the formation of biofilms, including Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica and Vibrio cholerae.

But Orr and her colleagues are the first to identify the molecule that completes the process of clearing c-di-GMP from the cell, thus ending the biofilm signaling process. The molecule is an enzyme called oligoribonuclease, and much like c-di-GMP, oligoribonuclease is also common among disease-causing bacterial species.

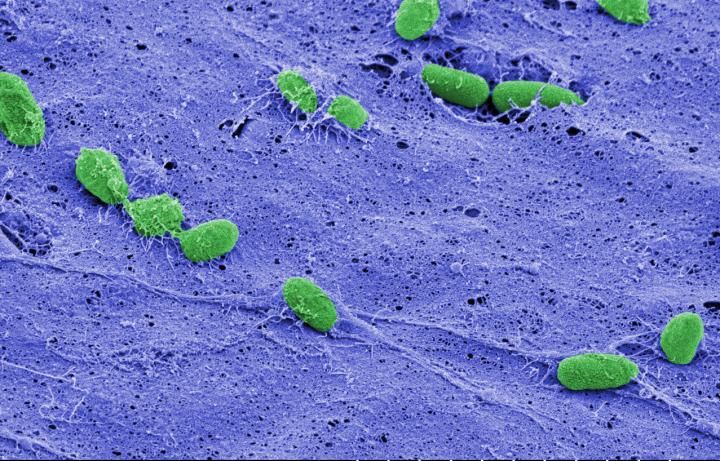

The team studied the process in the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Because of the genetic and physiological similarities between P. aeruginosa and other infectious species, the researchers believe that oligoribonuclease serves the same function across a wide variety of bacteria.

"You can think of this process in terms of water filling a sink. The rate of water from the faucet is just as important as the size of the drain in determining the level of water in the sink," said Vincent Lee, a co-author of the study and an associate professor in the UMD Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics and the Maryland Pathogen Research Institute. "The level of c-di-GMP in the cell is analogous to the amount of water in the sink. Because no one knew what the drain was, our findings create a complete picture of the signaling process."

The team found that oligoribonuclease is necessary for the second of a two-step process. The first, which converts c-di-GMP into an intermediate molecule called pGpG, was already known. Orr, Lee and their colleagues have now filled in the important second step in this process: oligoribonuclease breaks apart pGpG and thus completely shuts off the signaling pathway.

The result suggests that oligoribonuclease could be used to help design new antibiotics, disinfectants, and surface treatments to control biofilms. Such measures could prevent infections and preclude the need for frequent replacement of expensive hospital equipment. Because biofilms can also form on implanted medical devices, such as pacemakers and synthetic joints, effective treatments against biofilms could eliminate the need for costly and risky replacement surgeries.