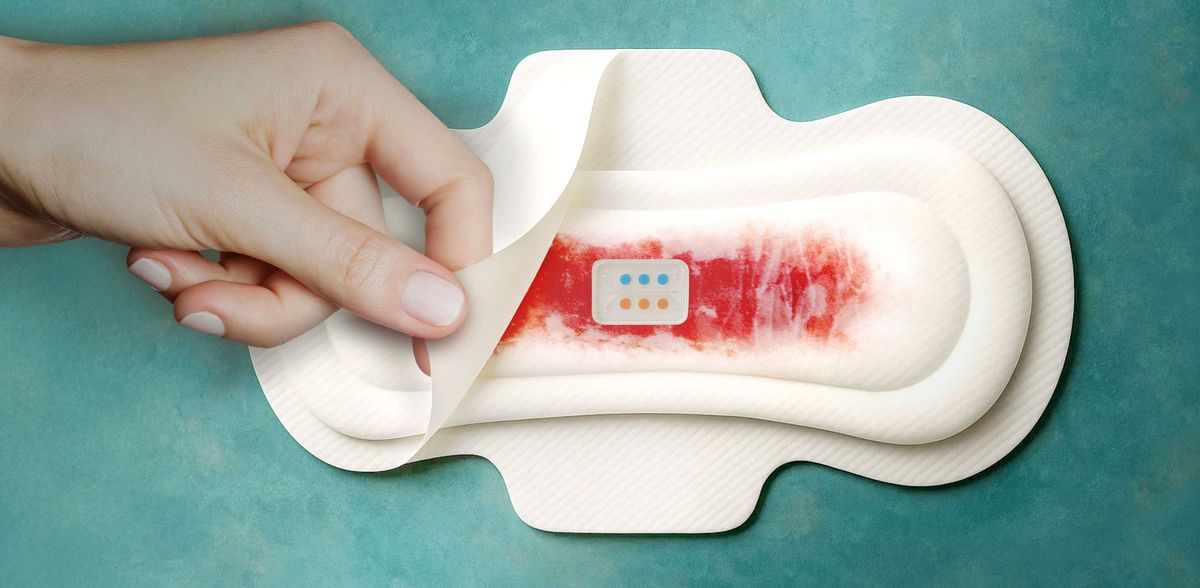

Sanitary towels morph into test strips

The electronic-free sensor technology does not rely on a laboratory and could facilitate the early detection of diseases in everyday life

Advertisement

Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed the first technology that is able to recognise biomarkers in menstrual blood – directly in sanitary towels. MenstruAI promises a simple, non-invasive method for recording health data in everyday life.

The application is very simple: wear the sanitary towel with the integrated non-electronic sensor, take a picture of the used towel with your smartphone and use the app to analyse it. MenstruAI is designed to enable users to check their health regularly and effortlessly. For the first time ever, a new technology from ETH Zurich is bringing a tracking tool to a place where hardly anyone would expect it: the sanitary towel.

Menstrual blood is a source of information

Over 1.8 billion individuals menstruate, yet menstrual blood hardly plays any role in medicine. “This reflects a systemic lack of interest in women’s health,” states Lucas Dosnon, first author and doctoral student in the group of Inge Herrmann, a professor at the University of Zurich, Balgrist University Hospital, Empa and accredited at the Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering at ETH Zurich.

“To date, menstrual blood has been regarded as waste. We are showing that it is a valuable source of information,” says Dosnon. Menstrual blood contains hundreds of proteins, and for many of them there is a correlation with their concentration in venous blood. Numerous diseases, including tumours such as ovarian cancer or endometriosis, lead to the presence of certain proteins in blood, which can serve as biomarkers for disease detection.

The ETH researchers used three biomarkers as a starting point for MenstruAI. They currently record the C-reactive protein (CRP) as a general inflammation marker, the tumour marker CEA typically elevated in all kinds of cancers and CA-125, a protein that can be elevated in endometriosis as well as in ovarian cancer. Many more protein-based biomarkers are being currently investigated and will be added to the list to reflect many other aspects of an individual’s health.

The same functionality as a Covid test

MenstruAI makes use of a paper-based rapid test strip, a principle that is also familiar from Covid self-tests – however, this time analysing blood instead of saliva. When the biomarker in the menstrual blood comes into contact with a specific antibody on the test strip, a coloured indicator appears. This varies in colour intensity depending on the concentration of the corresponding protein. The higher the concentration, the darker the colour will be. The test area is embedded in a novel small flexible silicone chamber, which can be combined with a commercially available sanitary towel. Thanks to its innovative nature, only a controlled volume of blood reaches the sensor – without smearing or falsifying the test.

The results can be read with the naked eye or with a specially developed app based on machine learning that evaluates the colour intensity. “The app also recognises subtle differences, such as the amount of proteins present, and makes the result objectively measurable,” explains Dosnon.

Does it actually work in everyday life?

Following an initial feasibility study with volunteers, the researchers are now planning a larger field study involving over one hundred people. The aim is to test the suitability of MenstruAI for everyday use under real-life conditions and to compare the values measured with established laboratory methods.

Another focus is on the biological diversity of menstrual blood: the composition varies depending on the day of the cycle as well as between individuals. This heterogeneity must be recorded and analysed – a pivotal step for clinical validation. Moreover, regulatory requirements must also be checked with a view to possible market authorisation, for example, biocompatibility must be assessed. The materials involved, however, are considered safe.

At the same time, the team is working with design experts from the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK). The aim is to further optimise the user experience, thereby keeping the psychological barrier as low as possible. “It’s also about designing the technology in such a way that makes it technically and socially acceptable,” says Herrmann.

Inexpensive, but no substitute for medical advice

The technology integrated within the pad works without laboratory equipment. “Right from the outset, the aim was to develop a solution that can also be used in regions with poor healthcare provision and would be as cost-effective as possible, potentially enabling population-based screening,” says Herrmann.

Consequently, MenstruAI can serve as an early warning system – users can seek medical advice in the event of abnormal values. It is not intended to replace established diagnostics, but to provide information on when a visit to the doctor's might be expedient. In addition, health progression can be monitored over the long term and any changes can be better understood.

Herrmann and Dosnon regard MenstruAI as more than just a technical project. It is a contribution to more equitable healthcare. “When we talk about healthcare, we can’t simply phase out half of humanity,” Herrmann underlines. The researchers were amazed at the extent to which the topic of menstruation is still stigmatized, including in academic circles, and that many declared their idea to be nauseous or impractical. Dosnon is convinced, however: “Courageous projects are called for to break down existing patterns of behaviour to ensure that women’s health finally takes the place it deserves.”