Genes found linked to breast cancer drug resistance could guide future treatment choices

Advertisement

Researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have discovered a gene activity signature that predicts a high risk of cancer recurrence in certain breast tumors that have been treated with commonly used chemotherapy drugs. Despite their resistance to drugs of the anthracycline class, the breast cancers bearing this gene signature will probably still be vulnerable to other types of chemotherapy agents, say scientists in a letter to be published in Nature medicine. Thus, the findings could lead to a genetic test of breast cancers to help physicians choose the best initial treatment for an individual patient.

With this guidance, physicians could avoid the current trial-and-error approach that in some cases exposes patients to the toxic side effects of a cancer drug that is destined to be ineffective. The new report underscores the potential of personalized cancer care, in which knowing the specific molecular features of a patient's cancer helps direct the course of care.

The investigators from the Dana-Farber Women's Cancers Program undertook the studies to search for molecular traits in tumors that cause some patients to suffer recurrences in the wake of breast cancer surgery despite post-surgery, or "adjuvant," chemotherapy, while other patients do well for many years.

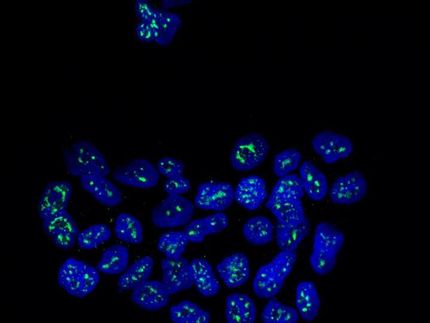

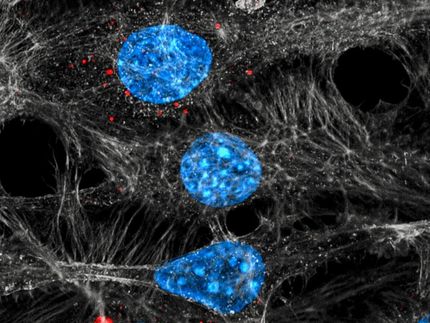

Led by Andrea Richardson, MD, PhD, and Zhigang Charles Wang, MD, PhD, the investigators identified two genes that, when abnormally active, enabled cancer cells to resist the effects of drugs called anthracyclines. This class of agents includes doxorubicin, daunorubicin, and epirubicin, which are often used as adjuvant therapy in breast cancer.

The scientists probed stored breast tumor specimens from 85 patients and found the gene signature associated with drug resistance in about 1 in 5 samples, according to the report. Clinical records on file showed that those patients had poorer outcomes than those without the culprit gene signature.

However, the overexpression of the two genes did not protect laboratory-grown breast cancer cells against other classes of drugs, including paclitaxel and cisplatin, reported Richardson, Wang, and the first author, Yang Li, PhD.

"These results suggest that tumors resistant to anthracyclines may still be sensitive to other agents," said Richardson, who is also on faculty at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School. "So this would be very useful as a test to help pick the therapy that's going to be most effective for these patients."

Such a tool should not be difficult to develop, she said, and could be available for clinical testing within a year or two.