Gene therapy for Parkinson's Disease moves forward in animals

Advertisement

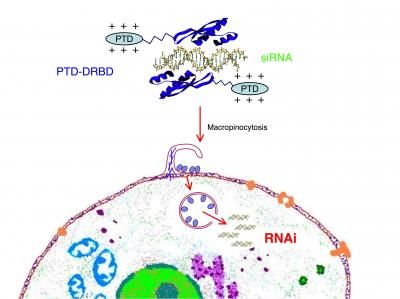

An international team of scientists has used gene therapy in two separate studies to renew brain cells and restore normal movements in monkeys and rats with a drug-induced form of Parkinson's disease. The research, detailed online in the scientific publications Brain and The Journal of Neuroscience, essentially describes one strategy to halt Parkinson's disease at its onset and another strategy to treat the devastating side effects that occur when treating the disease in its later stages.

By inserting corrective genes into the brain, scientists studying small monkeys called marmosets prevented brain damage by producing therapeutic levels of a protein that helps nourish brain cells, said Ron Mandel, a scientist with the University of Florida's McKnight Brain Institute and Genetics Institute.

The protein, called GDNF, short for glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor, is believed to preserve brain cells and could provide protection against Parkinson's disease. But its use has been debated since trials in humans ended last year without showing clinical improvements. Amgen conducted the trials and later halted use of the drug because of safety concerns, creating an outcry from hopeful Parkinson's patients.

But the gene therapy used in monkeys represents a different way to deliver the GDNF to the brain, causing the body to produce it naturally. It also produces more manageable levels of the protein in the brain.

"Our strategy is a neuroprotective concept and would only be amenable for early stage patients to keep a good quality of life. It would be a huge change in the way treatment is done," said Mandel, a neuroscientist in UF's College of Medicine. "We know the GDNF protects the neurons in primates from the model that we use, so that's good. We now know we can use very low doses that are still effective, so that's good. But we need a safety net. Once we turn it on, it's on for life. So we have to control it, and we're working on this as we speak. But it's not ready for clinical trials."

Parkinson's disease is caused by the death of brain cells that produce a vital chemical known as dopamine, which carries messages that tell the body how and when to move. In tests with 31 monkeys, including a control group, scientists inserted copies of a gene to produce GDNF into a region in the front part of the brain called the striatum. They then induced Parkinson-like conditions by introducing a drug to destroy the dopamine-producing cells. Seventeen weeks after that, not only did the GDNF-treated monkeys show improvement in performing tasks, analysis of brain tissue showed the animals' dopamine systems were actually spared by the treatment.

Meanwhile, in separate experiments with rats, researchers used gene therapy to completely reverse abnormal movements called dyskinesias in some of the animals, suggesting a new way to combat the flailing movements produced by a widely used drug treatment for Parkinson's disease. Levodopa, considered the gold standard of current treatment, enables the brain to replenish its dwindling supply of dopamine, sidetracking the destructive course of Parkinson's disease. But eventually the treatment can backfire. Scientists used 33 animals with severe dopamine depletion and transferred a gene to provide a source of L-dopa production into the animals' striata. Before receiving the treatment, all animals had limited use in their left paws. After treatment, the animals receiving the therapeutic enzyme mixture show complete recovery in their paws. Researchers say not only did the rats recover substantial degrees of function in their impaired forelimbs, continuous levels of L-dopa were being produced in their brains, blocking side effects.

About a half million Americans struggle with Parkinson's disease, including former Attorney General Janet Reno, former heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali and film star Michael J. Fox, according to the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Pope John Paul II was recently hospitalized because of breathing problems that were complicated by his advancing Parkinson's disease.

The recent findings in laboratory animals were a joint effort of Lund University in Lund, Sweden, the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, and the McKnight Brain Institute and the Genetics Institute of the University of Florida.

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Gene therapy

Genetic diseases once considered untreatable are now at the center of innovative therapeutic approaches. Research and development of gene therapies in biotech and pharma aim to directly correct or replace defective or missing genes to combat disease at the molecular level. This revolutionary approach promises not only to treat symptoms, but to eliminate the cause of the disease itself.

Topic world Gene therapy

Genetic diseases once considered untreatable are now at the center of innovative therapeutic approaches. Research and development of gene therapies in biotech and pharma aim to directly correct or replace defective or missing genes to combat disease at the molecular level. This revolutionary approach promises not only to treat symptoms, but to eliminate the cause of the disease itself.