Leading Ebola researcher at UTMB says there's an effective treatment for Ebola

Advertisement

A leading U.S. Ebola researcher from the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston has gone on record stating that a blend of three monoclonal antibodies can completely protect monkeys against a lethal dose of Ebola virus up to 5 days after infection, at a time when the disease is severe.

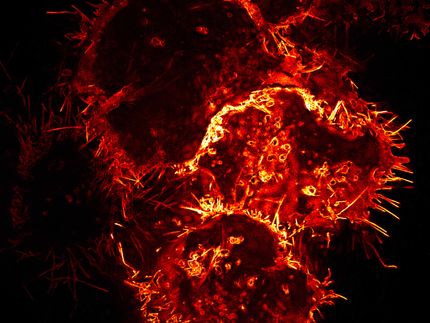

Thomas Geisbert, professor of microbiology and immunology, has written an editorial for Nature discussing advances in Ebola treatment research. The filoviruses known as Ebola virus and Marburg virus are among the most deadly of pathogens, with fatality rates of up to 90 percent.

Since the discovery of Ebola in 1976, researchers have been actively working on treatments to combat infection. Studies over the past decade have uncovered three treatments that offer partial protection for monkeys against Ebola when given within an hour of virus exposure. One of these treatments, a VSV-based vaccine was used in 2009 to treat a laboratory worker in Germany shortly after she was accidentally stuck with a needle possibly contaminated by an Ebola-infected animal.

Further advances have been made that can completely protect monkeys against Ebola using small 'interfering' RNAs and various combinations of antibodies. But these treatments need to be given within two days of Ebola exposure.

"So although these approaches are highly important and can be used to treat known exposures, the need for treatments that can protect at later times after infection was paramount," said Geisbert.

Further research led to a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies that protected 43% of monkeys when given as late as five days after Ebola exposure, at a time when the clinical signs of the disease are showing.

The new study from Qui and colleagues at MAPP Biopharmaceutical Inc. used ZMAPP to treat monkeys given a lethal dose of Ebola. All of the animals survived and did not show any evidence of the virus in their systems 21 days after infection, even after receiving the treatment 5 days after infection. They also showed that ZMAPP inhibits replication of the Ebola virus in cell culture.

ZMAPP has been used to treat several patients on compassionate grounds. Of these, two US healthcare workers have recovered, although but whether ZMAPP had any effect is unknown, as 45% of patients in this outbreak survive without treatment. There were also two patients treated with ZMAPP who did not survive, but this may be because the treatment was started too late in the disease course.

"The diversity of strains and species of the Ebola and Marburg filoviruses is an obstacle for all candidate treatments," said Geisbert. "Treatments that may protect against one species of Ebola will probably not protect against a different species of the virus, and may not protect against a different strain within the species."

Although we certainly need treatments for filovirus infections, the most effective way to manage and control future outbreaks might be through vaccines, some of which have been designed to protect against multiple species and strains. During outbreaks, single-injection vaccines are needed to ensure rapid use and protection. At least five preventative vaccines have been reported to completely protect monkeys against Ebola and Marburg infection. But only the VSV-based vaccines have been shown to complete protect monkeys against Ebola after a single injection.

"Antibody therapies and several other strategies should be included in the arsenal of interventions for controlling future Ebola outbreaks," said Geisbert. "Although ZMAPP in particular has been administered for compassionate use, the next crucial step will be to formally assess its safety and effectiveness."