Calcium in the nucleus renders neurons chronically sensitive to pain

Advertisement

Heidelberg pharmacologists and neurobiologists have discovered a key mechanism for the origin of chronic pain. In patients with persistent pain, calcium in the neurons ensures that these cells establish more contact to other pain-conducting neurons and react more sensitively to painful stimuli on a long-term basis. The identification of these changes in the spinal cord explains for the first time how the pain memory is formed. The results, which were published in the journal Neuron, have opened up new prospects for treating chronic pain.

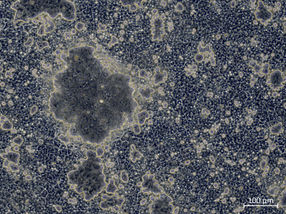

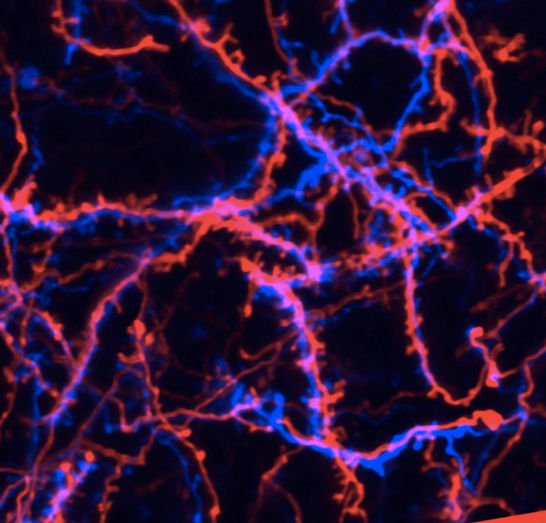

More networking than is needed: During long-term pain, calcium in the nucleus of neurons ensures that they establish more contacts to other pain-conducting neurons. This discovery by Heidelberg researchers explains how the pain memory is formed in the spinal cord. The image shows offshoots of neurons (red and blue) with the node-like contact sites (synapses).

Heidelberg University Hospital

The comprehensive research project is a joint achievement of the working groups led by Prof. Rohini Kuner, Director of the University of Heidelberg’s Deaprtment of Pharmacology, and Prof. Hilmar Bading, Director of the University of Heidelberg’s Interdisciplinary Center for Neurosciences (IZN).

Persistent severe pain, such as pain caused by chronic inflammation, nerve injuries and damage, herniated disks or tumors, often leaves its mark on the nervous system. Even if the original trigger has healed, minor stimuli such as brushing against the skin can already call up the former pain state, since the body has established a “pain memory.” To date, no satisfactory treatment has been available for patients with chronic pain, which affects several million people in Germany.

Blocking calcium in the cell nucleus prevents a pain memory from developing

The network of neurons in the body translates painful stimuli such as heat, cold, strong pressure or injuries into electrical signals which are conducted via the spinal cord to the brain and are perceived as pain there. In the case of chronic pain, the neurons in the spinal cord that transmit the pain are activated by weak signals themselves. They amplify the signals and transmit them to the brain as a pain stimulus. “Our research work performed in recent years has taught us a great deal about how neurons in the injured tissue are sensitized and then modify their activity,” explained Prof. Kuner. “However, these rapid and temporary processes cannot explain the long-lasting nature of chronic pain.”

The team led by Prof. Kuner and Prof. Bading discovered the solution to the enigma in the form of a universal neurotransmitter required by the neurons for every signal transmission: calcium. When an electrical signal arrives, the neurons in the spinal cord take up calcium from their environment and, in so doing, are activated. The researchers discovered that when patients have very strong or persistent pain, so much calcium enters the cells that it is transported into the cell nucleus, which is otherwise not the case. Once there, it influences the manner in which the areas of the genetic material (genes) are activated or deactivated. Mice in which the effect of the calcium in the cell nucleus is blocked in the neurons did not develop hypersensitivity to painful stimuli or a pain memory despite chronic inflammation.

Genes regulated by calcium are the key to chronification

“These genes regulated by calcium in the spinal cord are the key to the chronicity of pain, since they can trigger permanent changes,” said Prof. Kuner confidently. One of these changes was a family of genes (complement system) which previously had only been linked to inflammatory processes of the immune system. In the spinal cord neurons, these genes ensure that the processes form only a certain number of contact sites (synapses) to other neurons. In this way, the networking and, in turn, the intensity of the signal transmission is limited. Laboratory tests on neurons demonstrated that if the complement system is deactivated by calcium, additional synapses are formed, and the cell becomes more sensitive. “This structural change in the cell contacts can explain the permanent nature of a number of pain disorders,” said Kuner.

“Calcium signals in the neuronal nucleus are becoming increasingly significant for controlling brain functions. They are a type of universal switch that is always used when brain activity, e.g., during learning processes, leads to the development of long-term memory,” explained Prof. Bading. “Now our study is demonstrating that the same switch can also convert pain to a chronic state.” These findings and the identification of key genes, whose production is triggered by the nuclear calcium signal, offer new starting points for preventing the genesis of chronic pain in the future.