Asterix's Roman foes -- Researchers have a better idea of how cancer cells move and grow

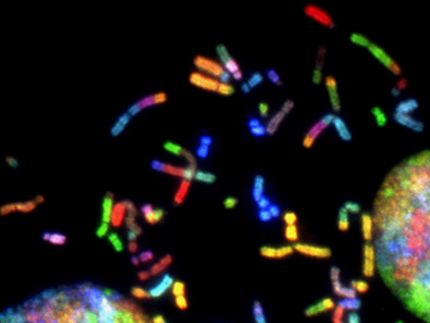

In a number of biological processes, including in the formation of metastases, cells communicate with each other in order to move as a group

Advertisement

Researchers at the University of Montreal's Institute for Research in Immunology and cancer (IRIC) have discovered a new mechanism that allows some cells in our body to move together, in some ways like the tortoise formation used by Roman soldiers depicted in the Asterix series. Collective cell migration is an essential part of our body's growth and defense system, but it is also used by cancerous cells to disseminate efficiently in the body. "We have found a key mechanism that allows cells to coordinate their movement as a group and we believe that this mechanism is used by malignant cells in a number of cancers, including some types of breast, prostate and skin cancers" explained lead researcher Gregory Emery. Roman soldiers formed the tortoise, or testudo formation, by coming closely together and aligning their shields side-by-side in order to defend themselves as they broke their enemy lines.

Researchers at the University of Montreal's Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer (IRIC) have discovered a new mechanism that allows some cells in our body to move together, in some ways like the tortoise formation used by Roman soldiers depicted in the Asterix series.

Université de Montréal

"As for the Romans, if some cancerous cells are migrating efficiently, it is because their movements are tightly coordinated. To stop their progression, we have first to understand how they coordinate. Then, we will aim at blocking this coordination in cancer cells to abrogate cancer progression."

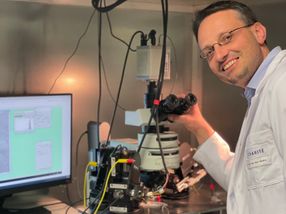

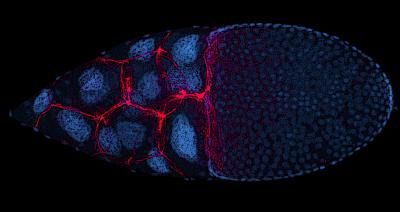

IRIC's scientists and their colleagues from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, USA studied the movement of the "border-cells" in the ovaries of fruit flies, a biological process that is well understood by scientists and that they can reproduce easily. Researchers often use these kinds of cells as a model to get insight into metastatic cell migration – the process by which malignant cells leave the original tumor– as they can be easily manipulated and observed. Researchers look at how chemicals known as proteins that our body produces influence what goes on in cells. In this study for instance, the researchers from IRIC were able to aim a laser with sufficient precision to activate or inactivate an engineered protein in a single living cell, and observe directly the consequences of these alterations.

They found that a protein known as Rab11 enables individual cells to sense what the others are doing and organize into a tight structure to move together. Rab11 achieves this by regulating another protein, called Moesin which is involved in controlling the shape and rigidity of cells. Reducing the level of Moesin reduces the cohesion of the cluster and impedes cell movement. "Here, we have identified a mechanism by which the cells share information to coordinate movements. By disrupting this mechanism, we are able to block their migration." Dr Emery explained.

Although the findings were in a specific kind of cells in an insect model, the proteins involved, Rab11 and Moesin, have already been shown to play a role in some human cancers. "This indicates that the new regulatory mechanism we identified in fly cells is most likely also important in human cancers," Dr. Emery said. "Our work will allow us to identify molecular targets to disrupt collective cell migration and hopefully to fight metastasis formation" he concludes.