An organic shoe grown from bacteria

Research team wants to initiate the transition to a sustainable fashion industry with new process thinking and innovative technologies

Advertisement

Shoes and trousers growing three-dimensionally from a nutrient solution. A robot mends a hole in a jacket and a tailor helps make it more fashion-forward, and all that for the cost of just a few euros. A Linz-based research team from the spheres of fashion and technology, creative robotics and biomechatronics seeks to kick off the transition to a sustainable fashion industry by means of new processual approaches and innovative technologies.

Right now, they are still slimy little bits left over from basic research experiments. But shirts and pants made from bacterial cellulose, grown in a laboratory in Linz, are the first visionary step towards application.

© Fashion and Robotics

Fair fashion, slow fashion, local production, and circular economy instead of tons of textile garbage. Environmentalists are not the only ones to call for changes in the resource-intensive textile industry. New EU directives also aim to contribute to the sustainable development of the global textile value chain. It is a stony road, however, as Christiane Luible-Bär reports. A fashion designer by training, she started her first sustainability project in Zurich in 2009, when she was just about to complete her doctorate: “With the support of 35 major partner companies from the fashion industry, we tried to have a robot sew a suit. The attempt failed, however, because the material and cuts for different body shapes make the manufacturing process very complex. Even today, automation is only possible for simple T-shirts, which is why clothes are still produced manually by sewing machine in low-wage countries.”

The solution is three-dimensional

Johannes Braumann, an architect by training, conducts research in the field of creative robotics at the University of Art and Design Linz. He sees strong parallels between fashion and architecture: “Both sectors are confronted with sustainability requirements, the need for automation and individual production of small batch sizes. The novel aspect of our research approach is that we start by taking a step back: instead of using automation to make an existing process as efficient as possible, we try to rethink the process in a completely open and new way.”

Having immediately convinced Luible-Bär, this approach to creative robotics became the core of the FWF-funded PEEK project “FAR – Fashion and Robotics”: instead of optimizing textiles and two-dimensional patterns, the project aimed to create 3D processes and new materials for the fashion industry. “We wanted to show a new approach and get away from the old maxim that you need ‘a fabric, a pattern and a sewing machine’,” explains principal investigator Luible-Bär. As a first step, the team had robots produce a garment using 3D printing. They also developed robotic arms that can cut or sew in three dimensions.

A new approach to darning holes

Over the course of the project, which ran for almost four years, the discussion about sustainable fashion increased in importance and the interdisciplinary team began looking for more revolutionary approaches. One example is the electrospinning process they developed for repairs to replace traditional “darning”. Braumann explains how it works: “In a high-voltage field, a robot arm sprays a polymer on the rip in a garment, and the polymer forms nanofibers that bond with the textile.” This application was presented at Ars Electronica 2023 in Linz and at Automatica in Munich.

The aim of this automation is to reduce the cost to around 2 euros, making repairs affordable and worthwhile again. At present, it is often cheaper to buy a new dress or a new pair of trousers. The approach also has advantages from a logistics point of view, notes Braumann: “First of all, electro spinning can be used in large factories, and when it involves quantities of hundreds of thousands it makes a big difference in terms of sustainability. Also, you can use a robotic arm that offers various functions and tools in urban areas as a micro-factory.”

The next step took the team from 3D repair to 3D redesign: if someone takes their five-year-old trousers to a tailor's shop for repairs, the tailor can work with the robot to make design suggestions to adapt them to the latest trend. In this way, garments would have a longer useful life and new job profiles would evolve. Christiane Luible-Bär, who is a lecturer at the University of Art and Design Linz, definitely supports such developments, as she also wants to give her students new perspectives.

Growing a shoe

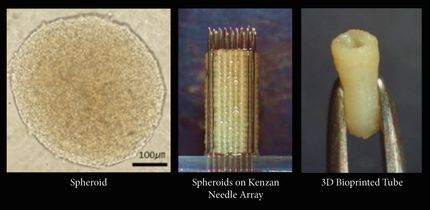

For the creative team, 3D printing was not the answer to everything; they also wanted to make fashion materials more sustainable. Werner Baumgartner from the Institute of Biomedical Mechatronics at the Johannes Kepler University was the ideal partner for completely rethinking another process: for the first time, the team succeeded in growing 3D trousers and 3D shoes – replacing the usual process of cutting and then sewing textiles. The newly developed biomaterials are not fiber-based, but grow three-dimensionally from bacteria, for example through a shoe last. The last has to be perforated so that the finished shoe can be removed. “The robot is also important in this case, but in a new role, namely as a food provider. The bacteria need to be supplied with a nutrient solution regularly at specific times, and a machine can feed them more reliably than a human,” says Luible-Bär. The team has now applied for a patent for this innovation that arose from their art-based research project.

In order to pursue their very forward-looking ideas, the researchers have applied for new EU research funding. In addition, the team has passed on know-how and findings to two guest researchers at the University of Art and Design in Linz.

A creative eye

Taking a creative but also pragmatic view of industrial processes requires changing perspectives, as Braumann explains: “Industry often has a tunnel vision aiming only at full automation. But we look at this differently and ask how much automation do we need at all? After all, we also want to give new value to craftsmanship.” In a large factory, for instance, it makes sense for an AI to scan the garments and identify spots that need repairs. A small alteration shop, on the other hand, does not need AI; there a human can mark the damaged area and the robotic arm then makes the cost-effective repair by means of electrospinning.

Luible-Bär corroborates this perspective: “Besides sustainability issues, it was important for us to have the creative aspect of the project. PhD students with an artistic focus conducted experiments on the interaction of robots, textiles and space, asking for instance: who is the active agent?” These are questions to be asked in the future: is the robot a helper or a co-creator? What do we expect from robots and how do we humans want to cooperate with machines?