Intestinal bacteria can harm the intestine

Researchers at Mainz University Medical Center investigate the role of the microbiome in the development of intestinal diseases

Advertisement

A research team from the Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis (CTH) at the University Medical Center Mainz has shown for the first time that intestinal bacteria can weaken the so-called intestinal barrier. In doing so, they inhibit the so-called Hedgehog signaling pathway. This pathway is largely responsible for the formation of a functioning intestinal barrier. The intestinal barrier controls the absorption of nutrients and prevents harmful substances from being absorbed. If it is disturbed, chronic inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer can develop. The research findings, published in the journal Nature Metabolism, are fundamental to developing new therapies for intestinal diseases.

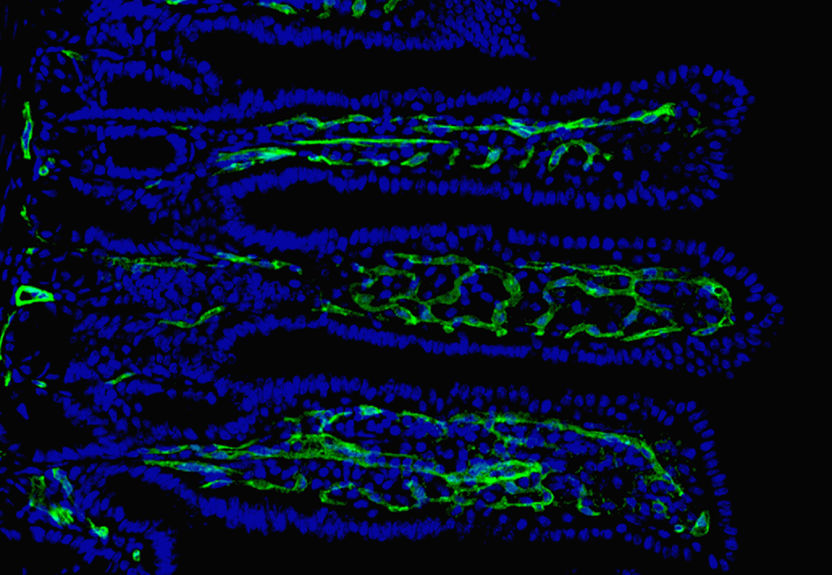

The image shows a microscopic image of small intestinal villi with capillary vessels (green) and cell nuclei (blue).

© Universitätsmedizin Mainz / Christoph Reinhardt

The intestine is home to more than 100 trillion bacteria - more than a person's body cells. The totality of microorganisms in the gut is also known as the microbiome or gut flora. The tasks of intestinal bacteria are manifold: for example, they help with digestion, prevent pathogens from colonizing and train the immune system. However, there are also bacteria that can cause flatulence or digestive problems, for example. Until now, it has not been known by what mechanisms the microbiome can influence the gut and its health.

"We were able to identify for the first time which signaling pathway is relevant for a stable intestinal barrier and how the intestinal microbiome can influence it. The strength of the intestinal barrier is determined by a mechanism in the intestinal epithelium called the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Gut bacteria can inhibit this important Hedgehog signaling pathway, weakening the intestinal barrier," explains Dr. Giulia Pontarollo, first author of the publication and a research associate at CTH.

In order to be able to identify the interactions of a bacterial species in detail among the trillions of intestinal bacteria, the Mainz researchers used a special method: so-called gnotobiotics. "With this method, we can decipher the interaction of bacteria with the organism by specifically investigating a single interaction under germ-free conditions in an animal model. This is the only way to distinguish beneficial from harmful bacteria," explains Univ. Prof. Dr. Christoph Reinhardt, working group leader at the Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis (CTH) at Mainz University Medical Center and member of the Gutenberg Research School (GFK).

The researchers found that the interaction of the bacteria with the intestinal barrier triggers a mechanism by which the protein neuropilin-1 is degraded in the intestinal epithelium. Without this important protein, the activity of the Hedgehog signaling pathway decreases. As a result, cell development is impaired and fewer stabilizing components are formed in the intestinal epithelium. The consequence: a weakened and permeable intestinal barrier.

In addition, the research team discovered that a deficiency of neuropilin-1 impairs the formation of vessels in the intestinal villi. These capillaries are particularly important for effectively absorbing nutrients.

"These new findings are essential to understanding how the microbiome promotes inflammatory responses in the gut and the development of colorectal cancer. Our goal is to transfer this knowledge into clinical research in order to be able to derive new therapeutic strategies in a targeted manner," says Professor Reinhardt.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.