Fighting colon cancer with killer cells

Advertisement

Genetically modified immune cells can successfully destroy colon cancer cells. This has been demonstrated for the first time by scientists from the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) at Georg Speyer House in Frankfurt using mini-tumors produced in the lab. They are making use of a new approach in cancer immunotherapy: genetically modified natural killer cells. Using patient-specific tumor cultures, scientists can now run tests in the lab to see how effective the killer cells will be in individual patients.

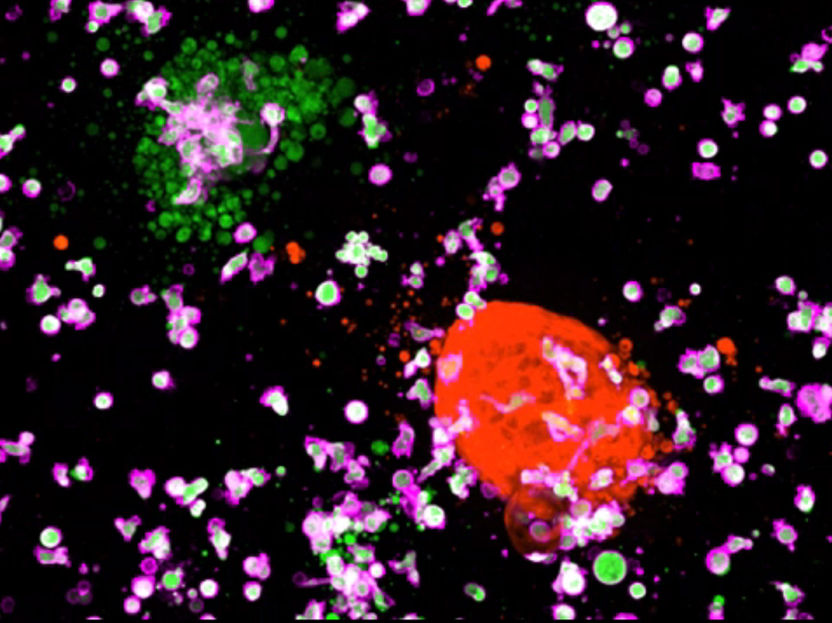

Killer cells attack: CAR-NK cells (violet), directed against a cancer specific surface protein, will only destroy colorectal cancer organoids (green) but not organoids with healthy colorectal cells (red).

© Henner Farin/Georg-Speyer Haus

For some years now, oncologists have had high hopes of immunotherapy methods that use genetically modified immune cells to specifically recognize and destroy cancer cells. Impressive success stories based on CAR T-Cells have already emerged in the treatment of B-cell lymphomas and leukemias. CAR T-Cells carry a genetically modified receptor that recognizes a tumor-specific target. CAR stands for chimeric antigen receptor. These types of CAR molecules are now being developed for natural killer cells (NK cells) as well. They can be obtained from the innate immune system, e.g. from healthy donor cells, which means that the NK cells do not have to be taken from each individual patient before being purified and reintroduced. They can also be used on anyone and it is rare for a patient to reject them.

Until now, however, CAR-NK cells have not often been used to fight solid tumors. "There are no suitable laboratory models to test systematically how effective different CAR-NK cell lines are for individual patients and what side effects they might have," explains Henner Farin, head of a DKTK young investigator group at Georg Speyer House in Frankfurt. At the moment, personalized therapy approaches are mainly tested on patient-specific mouse models carrying tumor tissue taken from patients. This poses challenges for preclinical trials, as Henner Farin explains: "Producing them is time-consuming and costly and the results are not completely transferrable to humans. Conventional cell cultures, on the other hand, cannot yet sufficiently replicate the complex tissue structure of solid tumors."

In the latest trial, he and his colleagues produced three-dimensional tumor cultures from tissue samples taken from patients with colorectal cancer. They tested these tumor organoids and organoids from healthy colon cells to see how effectively different CAR NK cell lines destroy colon cancer cells, and what damage they might cause – including in healthy cells. The scientists modified the mini-tumors genetically so that the cancer cells emitted measurable light signals. The more cancer cells were destroyed by the killer cells, the weaker the light signal became. Using this method, the scientists were able to observe live under the microscope how effectively and specifically the immune cells eliminated the cancer cells.

When the researchers directed the killer cells against a cell surface protein that is found in both abnormal and healthy cells, the tumor and normal organoids were attacked equally. By contrast, immune cells that were directed against a cancer-specific receptor protein destroyed only the cancer cells and did not attack any healthy cells. In this way, the scientists also discovered that FRIZZLED, a known signal receptor for CAR NK cell therapy, is not as effective as a target as was originally assumed. FRIZZLED is produced in particularly large quantities in certain colon cancer tumors. However, the anti-FRIZZLED killer cells also damaged the healthy organoids – an important finding for the development of therapies that target FRIZZLED.

The research team hopes the new system will speed up the development of personalized cancer immunotherapy. "The organoids are a patient's tumor avatar," says Henner Farin. "In future, we will be able to use this new system to assess how beneficial different CAR NK cell lines will be for patients and whether they are likely to suffer serious side effects." Tumor organoids can now be produced in the lab from tissue samples taken from lung tumors, breast cancer tumors and other solid tumors. This means that the screening method developed by the research team can in future be used to investigate the effectiveness of genetically modified killer cells for other types of tumor as well.

An approach using a similar basic principle to the CAR NK cell lines is currently being developed for clinical use in patients with malignant melanoma within the DKTK's "UniCAR NK Cells" joint funding project.