Tricks of Ticking time bomb Hepatitis B Virus

Advertisement

hepatitis B virus (HBV) causes hepatitis B, an infectious disease that afflicts 230 million people worldwide, thereof 440 000 in Germany. Persistence of the virus in liver cells leads to progressive organ damage in the patient and contributes to a high risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer development. Providing a new paradigm to hepatitis B understanding, researchers at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, Germany, and Department of Infectious Diseases, Molecular Virology, Heidelberg University Hospital have now uncovered a novel maturation mechanism employed by HBV to improve its infection success.

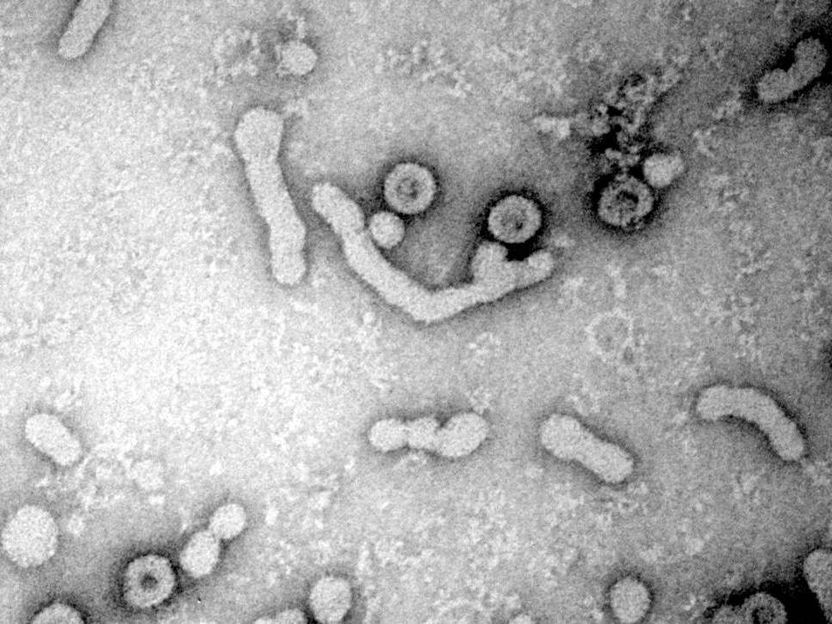

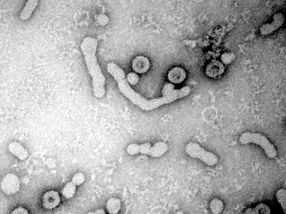

Electron micrograph of HBV virions released from infected cells. (large ovals with dark, center)

Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg / S.Seitz

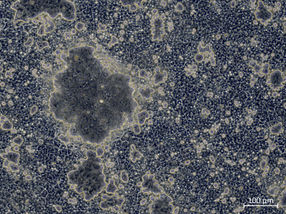

HBV (green) in liver cells (red): Only virions of the N-Type (left) are tranferred into the liver and are able to infect liver cells, HBV of the B-type (right) are not.

Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg / S.Seitz

To infect cells, viruses need to first attach to specific cellular receptors, i.e. molecules on the cell’s surface. In the case of HBV, a portion of the large surface protein (L protein) in the viral envelope binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) on the liver cell, and subsequently mediates uptake of the virus particle into the cell where progeny viruses are produced.

‘The effectiveness of HBV in establishing an infection is several orders of magnitude above that of most other animal viruses,’ describes Dr. Stefan Seitz, the lead author of the study. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that HBV is remarkably specific in infecting liver cells even after transmission of virus particles at extremely low number. Yet this presents a paradox, since HSPG are ubiquitously expressed across virtually all cell types in the human body. ‘For a virus which has to reach a target organ in far distance from the transmission site, HSPG seemed to be the most disadvantageous attachment receptors one could imagine,’ Seitz continues. So what might explain this discrepancy?

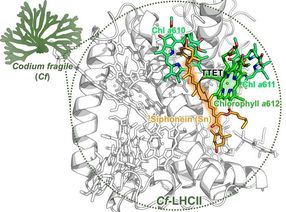

In tackling this question, the researchers were inspired by two past findings. First, cryo-electron microscope images of HBV showed that the virus appears in two morphologically distinct forms. Second, the L protein in the viral envelope can adopt two structural states. In one state, the receptor-binding determinant is oriented to the virus particle interior, in the other state it is exposed on the outer particle surface. The latter is required for the HBV infection process.

Seitz and colleagues believed that these two observations are linked, and hypothesized that HBV particles undergo a dynamic switch of their morphology during which they change the structural state of the L protein.

To investigate this, they established a biochemical method to differentiate the two groups of HBV particles, based on their binding abilities to HSPG: an ‘immature’, non-binding (N) type, and a ‘mature’, binding (B) type. Subsequent characterization showed that nearly all virus particles are released from the cells in the immature (N) state and spontaneously convert into mature (B) viruses over time by turning the receptor-binding determinant inside out across the viral membrane.

The maturation from N-type into B-type particles was determined to be a slow process rendering HBV infectious. Crucially, after injecting low numbers of virus particles into mice, the researchers found that N-types were superior over B-types in establishing infections in the liver, while B-type particles were prone to associate to multiple tissues outside the liver.

This slow maturation mechanism is believed to increase the effectiveness of HBV infection, and explains why liver cells are still targeted specifically even at low doses despite the widespread presence of HSPG on other organs. ‘In the immature N-type state the viral particles are inert and hence can cycle in the bloodstream continuously until they once reach the liver where they finally will be trapped. Conversion into mature particles afterwards will lead to a productive infection,’ Prof. Ralf Bartenschlager, Head of Division and second corresponding and last author of the study summarizes. ‘It is a novel and highly elegant paradigm for a viral maturation mechanism that differs fundamentally from all previously described viral maturation mechanisms. Our study also shows that HBV particles are not stiff and static objects, but highly dynamic nanomachines with a precisely running stochastic clockwork. Literally, they are little ticking time bombs which suddenly shoot out molecular grappling hooks.’

From a clinical point of view, Seitz and Bartenschlager believe this finding could provide another perspective to develop HBV combating drugs. ‘It offers the possibility to develop inhibitors of the maturation mechanism that lead to a “lock-in” or “freezing” of HBV particles in the immature, non-infectious state. Such inhibitors could be used to support therapy of chronic hepatitis B which is still incurable and represents a leading cause of cancer in mankind’ states Stefan Seitz.

With this discovery, the lab is now aiming to discover the exact molecular mechanisms and stimulus of the HBV maturation process, and also to identify inhibitors against it. ‘Obviously, breaking chronicity of HBV infection and eradicating the virus would reduce the risk of infected individuals to develop hepatocellular carcinoma’, Bartenschlager adds.