Comprehensive genetic characterization of primary immunodeficiency

Genetics of primary immunodeficiencies on an unprecedented scale explored

Advertisement

So-called primary immunodeficiencies (PID) are a group of rare immune system deficiencies, which are based on a malfunction of the immune system. Among other things, they can lead to recurring and often life-threatening infections in those affected. In addition, patients have an increased risk of autoimmune reactions, in which the immune system attacks the own body, as well as an increased risk of cancer. Primary immunodeficiencies are rare: it is estimated that one person in 10,000 is affected. They can differ considerably in characteristics and progression, which makes it particularly difficult to diagnose primary immunodeficiencies. The current assumption is that most of the PIDs are based on a genetic defect. Some genetic changes are inherited, and some develop spontaneously. But it is often difficult to determine a single gene mutation as the cause of the immunodeficiency, since not everyone with this gene mutation will suffer from the disease. An international research team involving researchers from the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology (IKMB) at Kiel University (CAU) has now presented a comprehensive genome analysis of PID patients which provides new insights into the genetic changes associated with PID. The team, led by researchers at Cambridge University, published their new findings this Wednesday in Nature.

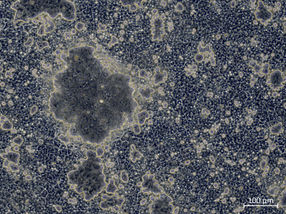

Through the detailed analysis of complete genomes of patients with a primary immune deficiency (PID), the researchhers were able to confirm a large number of rare gene alterations from previous studies and identify additional genes that are altered in diseased individuals compared to healthy individuals.

© Oliver Franke, IKMB Uni Kiel

Through detailed analysis of the whole genome sequencing (WGS) of patients, the researchers were able to confirm numerous rare gene mutations from previous studies into PID, and to identify additional genes that are mutated in patients but not in healthy people. Furthermore, changes to the genetic material in the so-called gene regulatory regions have been identified, which contribute to the development of diseases. Unlike other genes, these regions are non-coding - i.e. they do not contain the actual genetic coding for proteins - but instead regulate the expression of the other genes into proteins. The observed effect of changes to the gene regulatory regions provides an explanation for why the disease doesn’t occur in all people who carry known disease-causing gene mutations. The newly-identified genetic patterns of gene mutations that cause PID provide the basis for better genetic diagnosis of PID in the future. "This diverse disease has never before been investigated so comprehensively and with such depth of analysis, as in this new study," explained co-author Professor David Ellinghaus, a scientist at the IKMB and a member of the Cluster of Excellence "Precision Medicine in Chronic Inflammation" (PMI). "This represents an important step towards a more detailed understanding of the primary immunodeficiencies. The better we know the genetic causes of this disease, the better and more precisely we can diagnose and treat PID patients in the future," added Ellinghaus.

Based on analyses of the complete genomes of individual patients and their immediate relatives, the researchers investigated in detail how frequently-occurring, known gene variants together with rare gene variants have an impact on the immune system, and how they influence each other. For example, they analyzed the genome of a patient whose mother carried a rare gene variant and did not suffer from PID, but instead had an autoimmune disease. In addition to the rare gene variant inherited from their mother, the PID patient also inherited a common gene variant from their father, which has to date been associated with rheumatoid arthritis. In contrast, the brother of the PID patient only inherited the common gene variant from their father, and has no symptoms of PID. The joint influence of a common and a rare risk variant has presumably led to the severe immune system deficiency. This example illustrates why the characteristics and symptoms of the disease can vary so significantly from person to person, even within the same family.

Co-author Dr. Eva Ellinghaus, a scientist at the IKMB and a member of the Cluster of Excellence PMI, had already conducted prior international research work, together with other PMI cluster members, into the genetics of patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID, one of the most common forms of the PID group of disorders). The data was re-analyzed for the newly-completed study, and provided important additional insights into the genetics of PID. "At the time, our analysis was the largest genetic investigation into CVID. We genetically analyzed more than 770 patients and identified a new risk gene for the disease, called CLEC16A. In the current study, we have determined that genetic risk variants in CLEC16A increase the risk of both PID as well as autoimmune disorders," said Dr. Eva Ellinghaus.

On the basis of these new research findings, it could be possible in future to identify specific gene variants and genetic patterns in individual patients, through individual WGS analysis, and thereby better diagnose the presence of a PID disease than is currently possible. "The new study is an important step towards precision medicine, i.e. individualized medicine, for primary immunodeficiencies," said Prof. David Ellinghaus. "Because these diseases are so diverse in their expression and at the same time so rare, it is all the more important that each patient is treated individually," added Ellinghaus.