Researchers say lupus treatment shows early promise

Advertisement

A new treatment that may reverse the effects of the most common type of lupus has shown promising results after undergoing early testing by a team of researchers at University of Florida Health.

The findings of a two-year study that used human cells and mouse models were in Science Translational Medicine. The new treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus involves regulating metabolism in cells that affect how lupus develops in the body. It has yet to undergo clinical trial in humans.

Just as diet has a major effect on overall health, nutrients affect immune activity at the cellular level. Now, UF Health researchers may have found a way to rein in lupus by changing the way cells in the immune system use energy.

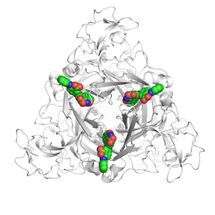

A key finding of the study involved the researchers characterizing the way specialized white blood cells known as CD4 T-cells use nutrients. In lupus, these cells used mostly glucose, a type of simple sugar, for energy metabolism. This seems to be critical in causing inflammation in the immune system and the tissue destruction that result from the disease. When the researchers blocked glucose metabolism by using the common type 2 diabetes drug metformin and a glucose inhibitor, the CD4 T-cells returned to normal activity and the symptoms of lupus were reversed.

The studies involved a number of mouse models of the disease and the key experimental findings were also observed in human CD4 T-cells from lupus patients.

The research team initially got the idea of using a two-pronged attack on lupus after seeing a similar approach succeed in cancer research, said Laurence Morel, Ph.D, director of experimental pathology and a professor of pathology, immunology and laboratory medicine in the UF College of Medicine.

“If it works to limit metabolism of cancer cells, it should work to limit metabolism in T-cells,” Morel said.

The treatment combination is especially effective in reversing lupus symptoms, the study found. It works by simultaneously preventing a T-cell from using glucose while also slowing the cell’s own metabolism, Morel said.

“If the T-cell is normal, the disease gets better,” she said.

The approach found by Morel and the other researchers goes beyond just controlling symptoms. Lupus-afflicted mice that were treated continuously for one to three months closely resembled those that did not have the disease, Morel said. The drug metformin’s effectiveness in restoring normal function in T-cells when studied in the laboratory also bodes well for its potential future application for treating patients with lupus.

“That suggests we can also use metabolic inhibitors to treat patients,” Morel said. “It’s the first time that it has been shown that you can have an effect on lupus symptoms and manifestation by normalizing cellular metabolism.”

The study is also significant for its breakthrough in “drug repurposing,” Morel said. Using an existing diabetes medication like metformin to treat lupus is relatively cost-effective and the drug is already known to be safe for humans. New treatments that use an existing medication can also go to clinical trials more quickly because there are fewer FDA regulatory hurdles.

Next, Morel said, researchers will continue their efforts in two directions. One involves screening additional inhibitors targeting other metabolic pathways as well as studying patients who have been treated with metabolic inhibitors. The other involves searching for a deeper understanding of the molecular pathways that make metformin work.