Alzheimer's disease risk linked to a network of genes associated with myeloid cells

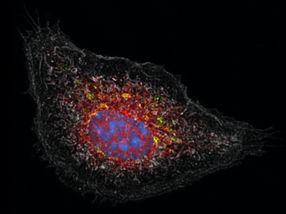

Many genes linked to late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD) are expressed in myeloid cells and regulated by a single protein, according to research conducted at the Icahn School of medicine at Mount Sinai.

Mount Sinai researchers led an international, genome-wide study of more than 40,000 people with and without the disease and found that innate immune cells of the myeloid lineage play an even more central role in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis than previously thought.

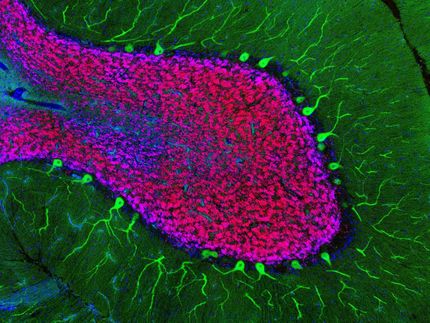

Specifically, the research team identified a network of genes that are implicated in AD and expressed by myeloid cells, innate immune cells that include microglia and macrophages. Furthermore, researchers identified the transcription factor PU.1, a protein that regulates gene expression and, thus, cell identity and function, as a master regulator of this gene network.

"Our findings show that a large proportion of the genetic risk for late-onset AD is explained by genes that are expressed in myeloid cells, and not other cell types," says Alison Goate, DPhil, Professor of Neuroscience and Director of The Ronald M. Loeb Center for Alzheimer's Disease at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and principal author of the study. "Dysregulation of this network is certainly a cause of Alzheimer's, but we have more work to do to better understand this network and regulation by PU.1, to reveal promising therapeutic targets."

Using a combination of genetic approaches to analyze the genomes of 14,406 AD patients, and 25,849 control patients who do not have the disease, researchers found that many genes which are known to influence the age at which AD sets in, are expressed in myeloid cells. This work pinpointed SPI1, a gene that encodes the transcription factor PU.1, as a major regulator of this network of AD risk genes and demonstrated that lower levels of SPI1/PU.1 are associated with later age at onset of AD.

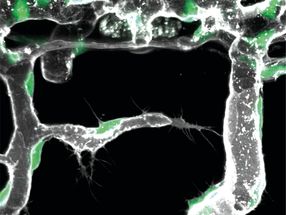

To test the hypothesis that SPI1 expression levels influence expression of other AD risk genes and microglial function, the researchers used a mouse microglial cell line, BV2 cells that can be cultured in a dish. When researchers knocked down expression of SPI1, the gene that produces PU.1 in cells, they found that the cells showed lower phagocytic activity (engulfment of particles), while overexpression of SPI1 led to increased phagocytic activity. Many other AD genes expressed in microglia also showed altered expression in response to this manipulation of SPI1 expression.

"Experimentally altering PU.1 levels correlated with phagocytic activity of mouse microglial cells and the expression of multiple AD genes involved in diverse biological processes of myeloid cells," says Dr. Goate. "SPI1/PU.1 expression may be a master regulator capable of tipping the balance toward a neuroprotective or a neurotoxic microglial function."

The researchers stress that because the PU.1 transcription factor regulates many genes in myeloid cells, the protein itself may not be a good therapeutic target. Instead, further studies of PU.1's role in microglia and AD pathogenesis are necessary, as they may reveal promising downstream targets that may be more effective in modulating AD risk without broad effects on microglial function. Increased understanding is crucial to facilitating the development of novel therapeutic targets for a disease that currently has no cure.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

From now on, don't miss a thing: Our newsletter for biotechnology, pharma and life sciences brings you up to date every Tuesday and Thursday. The latest industry news, product highlights and innovations - compact and easy to understand in your inbox. Researched by us so you don't have to.