Chestnut leaves yield extract that disarms deadly staph bacteria

The extract shuts down staph without boosting its drug resistance

A study showed the ability of a chestnut leaf extract to block Staphlococcus aureus virulence and pathogenesis without detectable resistance. The use of chestnut leaves in traditional folk remedies inspired the research, led by Cassandra Quave, an ethnobotanist at Emory University.

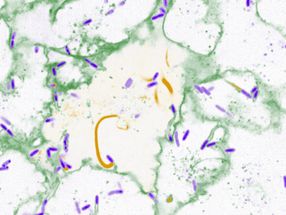

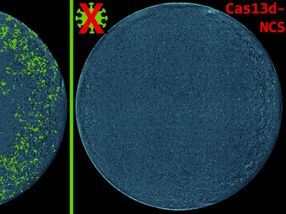

"We've identified a family of compounds from this plant that have an interesting medicinal mechanism," Quave says. "Rather than killing staph, this botanical extract works by taking away staph's weapons, essentially shutting off the ability of the bacteria to create toxins that cause tissue damage. In other words, it takes the teeth out of the bacteria's bite."

The discovery holds potential for new ways to both treat and prevent infections of methicillin-resistant S. aureus, or MRSA, without fueling the growing problem of drug-resistant pathogens.

"We've demonstrated in the lab that our extract disarms even the hyper-virulent MRSA strains capable of causing serious infections in healthy athletes," Quave says. "At the same time, the extract doesn't disturb the normal, healthy bacteria on human skin. It's all about restoring balance."

Quave, who researches the interactions of people and plants is on the faculty of Emory's Center for the Study of Human Health and Emory School of Medicine's Department of Dermatology. For years, she and her colleagues have researched the traditional remedies of rural people in Southern Italy and other parts of the Mediterranean. "I felt strongly that people who dismissed traditional healing plants as medicine because the plants don't kill a pathogen were not asking the right questions," she says. "What if these plants play some other role in fighting a disease?"

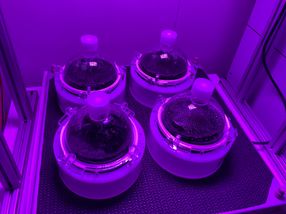

Hundreds of field interviews guided her to the European chestnut tree, Castanea sativa. "Local people and healers repeatedly told us how they would make a tea from the leaves of the chestnut tree and wash their skin with it to treat skin infections and inflammations," Quave says.

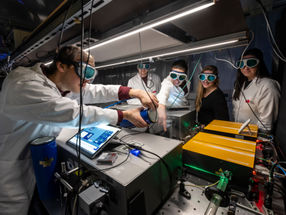

For the current study, Quave teamed up with Alexander Horswill, a microbiologist at the University of Iowa whose lab focuses on creating tools for use in drug discovery, such as glow-in-the-dark staph strains.

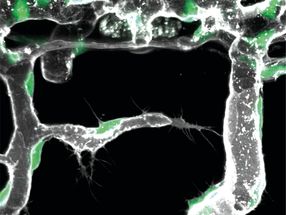

The researchers steeped chestnut leaves in solvents to extract their chemical ingredients. "You separate the complex mixture of chemicals found in the extract into smaller batches with fewer chemical ingredients, test the results, and keep honing in on the ingredients that are the most active," Quave explains. "It's a methodical process and takes a lot of hours at the bench. Emory undergraduates did much of the work to gain experience in chemical separation techniques."

The work produced an extract of 94 chemicals, of which ursene and oleanene based compounds are the most active.

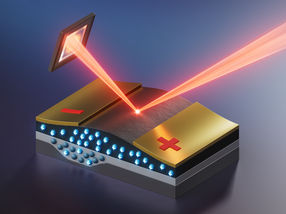

Tests showed that this extract inhibits the ability of staph bacteria to communicate with one another, a process known as quorum sensing. MRSA uses this quorum-sensing signaling system to manufacture toxins and ramp up its virulence.

Original publication

Cassandra L. Quave, James T. Lyles, Jeffery S. Kavanaugh, Kate Nelson, Corey P. Parlet, Heidi A. Crosby, Kristopher P. Heilmann, Alexander R. Horswill; "Castanea sativa (European Chestnut) Leaf Extracts Rich in Ursene and Oleanene Derivatives Block Staphylococcus aureus Virulence and Pathogenesis without Detectable Resistance"; PLOS One; 2015

Most read news

Original publication

Cassandra L. Quave, James T. Lyles, Jeffery S. Kavanaugh, Kate Nelson, Corey P. Parlet, Heidi A. Crosby, Kristopher P. Heilmann, Alexander R. Horswill; "Castanea sativa (European Chestnut) Leaf Extracts Rich in Ursene and Oleanene Derivatives Block Staphylococcus aureus Virulence and Pathogenesis without Detectable Resistance"; PLOS One; 2015

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

From now on, don't miss a thing: Our newsletter for biotechnology, pharma and life sciences brings you up to date every Tuesday and Thursday. The latest industry news, product highlights and innovations - compact and easy to understand in your inbox. Researched by us so you don't have to.