Why tumours exhibit fatty degeneration

In cases of clear cell renal cell carcinoma – the most common type of renal cell carcinoma – the cancer cells become fatty. The reasons for this were long unclear, but ETH researchers have now found the cause: important cell structures in lipometabolism degrade more rapidly.

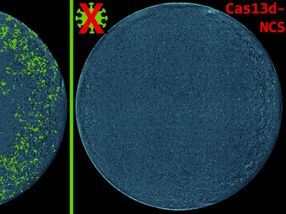

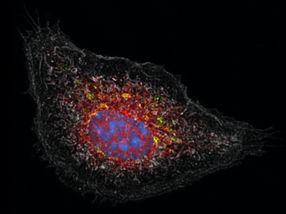

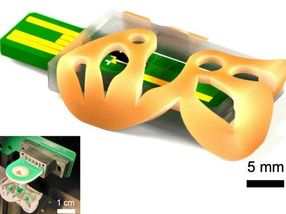

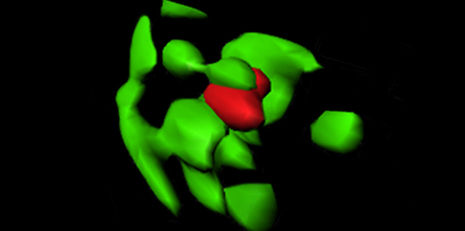

With cutting-edge microscopy technology (3D structured illumination microscopy) it can be shown how a peroxisome (red) is digested by a degrading cell structure (autophagasome, green).

Miriam Schönenberger / ETH Zürich

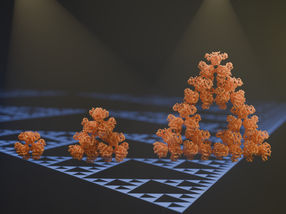

In kidney cancer and some other types of cancer, the tumours undergo fatty degeneration. With the most common type of cancer – clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC) – the affected cells, as the name indicates, are nearly transparent under the microscope due to the presence of a high level of fat. A team of researchers led by Wilhelm Krek, professor at the Institute for Molecular Health Sciences, investigated how this fatty degeneration occurs. In experiments on genetically modified mice and tissue samples from cancer patients, the researchers discovered that peroxisomes and a signal molecule called Hif2 play crucial roles in the process. Peroxisomes are intracellular structures and are among the key players in cellular lipometabolism; they break down fatty acids and other lipids, and the composition of certain other important lipids also takes place here.

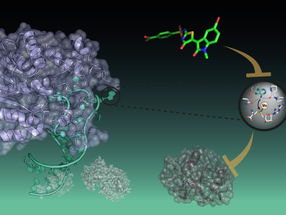

The researchers demonstrated that the Hif2 signal molecule, which human and animal cells produce more of when there is insufficient oxygen, controls the activity of peroxisomes. This happens through a process referred to as autophagy (self-digestion): if a peroxisome is damaged while it works, the cell segregates it and then breaks it down and replaces it with a new one. “Hif2 accelerates this process. If the concentration of Hif2 in the cell increases, more peroxisomes are destroyed than are formed,” explains Werner Kovacs, senior assistant in Krek’s group.

This type of Hif2 accumulation occurs in cancers, for example. When tumours grow very rapidly, their supply of nutrients and oxygen becomes scarce; as a result, Hif2 concentration in the tumour cells increases and more peroxisomes are destroyed, thus steering the lipometabolism in another direction. Meanwhile, the tumour tissue becomes fattier.

Excess Hif2 caused by genetic disorders

However, oxygen depletion is not the only trigger for the fatty degeneration of tumours. In further experiments on mice, the researchers discovered that the cells also produce excess Hif2 in certain genetic disorders. This is particularly true for the inherited Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, which occurs when what is known as a tumour suppressor protein is defective or missing. This protein normally prevents the development of cancer, but if it is missing it results in a disturbed lipometabolism, which leads to kidney cancer in many sufferers.

Now that researchers have discovered that the interaction between Hif2 and the peroxisomes causes tumour cell fatty degeneration, they want to clarify whether an overproduction or even a deficiency of specific lipid molecules contributes to tumour growth. In Kovacs’ view, this remains unclear. Further research should reveal the specific role of Hif2 in tumour cell lipometabolism – the ETH researchers are also interested in identifying lipid molecules biomarkers that could be used in the future to diagnose cancer.

Original publication

Original publication

Walter KM, Schönenberger MJ, Trötzmüller M, Horn M, Elsässer HP, Moser AB, Lucas MS, Schwarz T, Gerber PA, Faust PL, Moch H, Köfeler HC, Krek W, Kovacs WJ: Hif-2a Promotes Degradation of Mammalian Peroxisomes by Selective Autophagy. Cell Metabolism 2014. 22: 882-897

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

From now on, don't miss a thing: Our newsletter for biotechnology, pharma and life sciences brings you up to date every Tuesday and Thursday. The latest industry news, product highlights and innovations - compact and easy to understand in your inbox. Researched by us so you don't have to.